The Travels of a Journalistâ€â€ÂÂ59-Two nights in Olympic National Park make our journey home 10-day task

Posted on March 3rd, 2011

By Shelton A. Gunaratne ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚©2011 Professor of mass communications emeritus at ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ Minnesota State University Moorhead

ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ All good things must come to an end, the proverb asserts.

So did my stint with the (Longview) Daily News.

I had to be back in Minnesota in time for the beginning of fall term at my university in Moorhead. So weƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚daughter Carmel, 5; son Junius, 9; wife Yoke-Sim and IƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚left Longview Saturday (26 Aug. 1989) in our Toyota Camry station wagon via the Olympic Peninsula and the Trans-Canada Highway.

Because three of us had thoroughly enjoyed our forays into Sequoia and Yosemite national parks in 1983 before CarmelƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s birth (see Travels-18 and 20); and all of us had fond memories of our experiences in Voyageurs National Park in 1988 (Travels-48); and my solo adventure in Volcano National Park in 1984 (Travels-51), we wanted to start our return journey with a taste of the Olympic National Park (ONP) in Washington.

The 922,561-acre ONP intrigued us because of its divisibility into three basic geographical regions: the Pacific coastline, the Olympic Mountains and the temperate rainforest. In recognition of this unique three-dimensional combination, ONP became an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976. Five years later, UNESCO designated it a World Heritage Site.

President Theodore Roosevelt, an unabashed conservationist, created the Mount Olympus National Monument in 1909. In 1938, Congress authorized the parkƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s re-designation as a national park, and President Franklin Roosevelt signed the legislation approving the status change. In 1988, Congress designated 95 percent of ONP as the Olympic Wilderness.

Saturday morning, we got up early to empty the apartment of all our belongings and pack them into the boot of our car. After leaving the apartment, we went to the Longview Safeway for coffee. Then, we left Longview for good at 8 a.m. or so on our way to ONP.

Our first stop was the familiar city of Centralia, 45 miles to the north on I-5.

After filling up our car in Centralia, we headed 35 miles northwest on U.S.12 to Elma (pop. 3,049) in Grays Harbor County.

Driving 21 miles west of Elmer, we stopped at Aberdeen (pop. 16,461), known as the ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Gateway to the Olympic Peninsula.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ We visited the Aberdeen Museum of History. In the early 1900s, Aberdeen had the reputation of being ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-one of the grittiest towns on the West Coast, with many saloons, whorehouses, and gambling establishments populating the areaƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ (Wikipedia). We also tarried in the adjoining city of Hoquiam (pop.9, 097) to rush through the Polson Park and museum and HoquiamƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s Castle.

In the vicinity of Hoquiam-Aberdeen-Cosmopolis, where U.S. 12 merged with U.S.101, we drove north to reach the southern boundary of the Olympic National Forest right into Quinault (pop. 191), 44 miles to the north.

Access to the temperate rainforest division of ONP is possible through the Quinault, Queets, and Hoh/Bogachiel valleys on the western flank of the park. We entered the ONP through the Quinault Valley, also known as the ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Valley of the Rain Forest Giants.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚

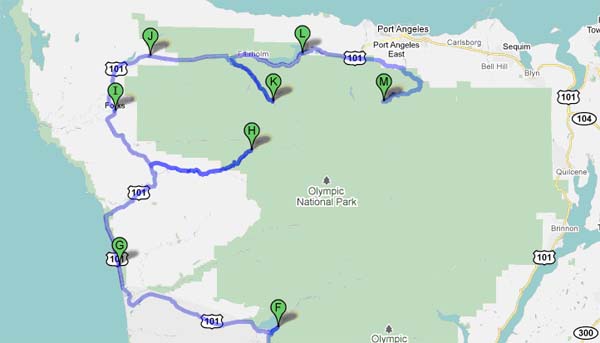

Figure 1: Olympic National Park Exploration Route:

A=Longview (not in map); B=Centralia; C=Elma; D=Aberdeen; E=Hoquiam/Grays Harbor; F=Quinault/Graves Creek; G=Kalaloch Lodge/Queets; H=Hoh Rain Forest Campgrounds and Visitor Center;

I=Forks; J=Sappho; K=Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort: L=Lake Crescent; M=Heart oƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢ the Hills Campgrounds/Hurricane Ridge.

Quinault Rainforest

ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ The temperate Quinault Rainforest dominates the entire valley. This glacially carved valley, comprising the 7.6 square-mile Lake Quinault and the 69-mile Quinault River, provides access to the second major division of ONP, the Olympic Mountains.

The Quinault Indian Nation owns Lake Quinault. The Quinault River marks the boundary of ONP for several miles before emptying into Lake Quinault. After the lake, the river flows southwest, reaching the ocean at TaholahƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚the approximate starting point of the third geographical division of ONP, the Pacific coastline.

[The Quinault Indian Reservation (pop. 1,370), encompassing a land area of 316.331 sq. miles, lies to the west of the lake. About 60 percent of the reservation’s population lives in the community of Taholah.]

A 30-mile scenic loop around Quinault lake and the river enables visitors to go on scenic drives to spot the flora and fauna peculiar to a temperate rainforest, particularly the Roosevelt elk, the largest land mammal in the park, which serves as a preserve for some 4,000 to 5,000 of these elk. Other protected fauna thriving in the parkƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s rainforest include the Pacific tree frog, Northern spotted owl, bobcat, cougar, raccoon, Olympic black bear and black-tailed deer.

The facilities flanking the Quinault River include the Quinault Rainforest Ranger Station on the North Shore and the Olympic National Forest/Park Information Station on the South Shore. The historic Lake Quinault Lodge and the Rain Forest Resort Village also stand on the South Shore.

The valley derives its nickname from the largest specimens of Western red cedar, Sitka spruce, western hemlock, Alaskan cedar and mountain hemlock, as well as five of the top 10 largest Douglas-firs, found in the forest. Other native flora that make the ONP Rainforest their home include the big leaf maple, vine maple, red alder and black cottonwood.

From Quinault, we cruised 17 miles northeast on the South Shore of the lake and the river all the way to idyllic Graves Creek, where the facilities include two campgrounds. The cliffs of Mount Hoquiam, Mount Olson and Mount Lawson surrounded us as we ate our lunch enjoying the superlative charm of nature.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ We couldnƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢t resist the temptation to hike about a half-mile on the Six Ridge Trail. However, we had to bear the inconvenience of continual drizzling endemic to rainforests.

We drove back on the same gravel road but shifted to the North Shore of the loop at North Fork. We rejoined U.S. 101at the southwestern edge of Lake Quinault and headed west to the coastal resort of Kalaloch, an unincorporated community, almost 50 miles from Graves Creek. We got off at the Kalaloch Lodge to walk along the Pacific Beach although it was chilly and foggy. The scenery varied from beaches (that might be sandy, rocky or boulder-strewn!) to cliffs plunging into the sea. Three national wildlife refuges and the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary protect the marine environment and offshore islands.

About five miles to the south of Kalaloch is the tiny Native American community of Queets, which provides access to ONPƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s Pacific Beach hiking trails.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚

From Kalaloch, we followed U.S. 101, which runs north and then turn northeast at the mouth of Hoh River bordering the 477-acre Hoh Indian Reservation (pop. 102). At the junction where U.S. 101 crosses the Hoh River to go northwest again, we turned east on Upper Hoh Road to reach the Hoh Rainforest Campground, just to the west of the Visitor Center, about 6.30 p.m. We drove 41 miles from Kalaloch to reach our destination of the day, translating to a driving stretch of 265 miles all the way from Longview.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚

Hoh Rainforest

Howsoever tiring our relentless tour was, we were delighted to have explored two of the three geographical dimensions of ONP, the temperate rainforest and the uneven terrain of the Pacific coastline. We werenƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢t fully prepared to explore the remaining dimension of ONP: the snow-capped peaks of the Mountains. Locations where snowy peaks sit side by side with rainforests are unusual.

Originating in the Ho Glacier on Mount Olympus (elev. 7,980 ft.), the Ho River flows 56 miles west and empties itself into the Pacific Ocean at the Hoh Indian Reservation.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ The final segment of the Ho River marks the boundary between the ONP and the Indian reservation while also providing another point of road access to the rainforest in the Ho Valley.

The Hoh River Campground is the trailhead of the Hoh River Trail, which follows the river through the Hoh Rain Forest from the campground to Mount Olympus. The Hoh Rainforest accommodates the National Park Service Ranger Station, from where backcountry trails extend deeper into the national park.

A popular 0.8-mile loop trail near the visitor center is the Hall of Mosses, which gives visitors a feel for the local ecosystem. ItƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s a display of big leaf maple, Sitka spruce and other temperate conifers covered in green and brown mosses. Along the trail, a side path of 200 feet leads to a grove of maple trees covered with moss.

ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚

Maples in the Hall of Mosses Trail at Hoh Rainforest (August 2006)

Maples in the Hall of Mosses Trail at Hoh Rainforest (August 2006)

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Photo by Kevin Muckenthaler]

ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ Junius and I set up our tent in Campground A for our overnight stay. Later, after eating our dinner, all of us attended the rangersƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢ campfire program on ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Life style of the salmon on the Hoh, Queets and Quinault rivers.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚

ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ Day 2

We kicked off Sunday (27 Aug.) morning with a walk on the Hall of Mosses Trail. Then, we backtracked the Upper Hoh Road to head northwest on U.S. 101 to Forks (pop. 3,120) in Clallam County. The Forks Timber Museum did not exist at the time of our visit. However, we stopped in the town to buy groceries and get maps at the visitor center.

We spent the rest of the day with visits to:

- Sappho, where we toured the Sol Duc Hatchery. The hatchery exhibited big salmon in the adult pond, which was fascinating.

- Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-best known for its soaking pools, hot tubs, and a swimming pool that are heated with the nearby hot springs.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚

- Storm King Ranger Station at Crescent Lake. We ate our lunch here, and then we walked a one-mile trail to see the 90-foot Marymere Falls.

- Elwha River Valley to see Lake Mills formed by the Glines Canyon Dam (also known as Upper Elwha Dam), a 210-ft structure built in 1927. (Because the dam has drastically reduced the annual salmon run in the Elwha River watershed from more than 400,000 to less than 4,000 adult returns, the federal government has undertaken to decommission and demolish the dam starting 2011.)

- Pioneer Memorial Museum and Visitor Center in Port Angeles

From Port Angeles, we drove to our final destination of the day: the Heart OƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢the Hills Campground to set up our tent for our overnight stay. But we hardly expected the highlight of the day to come last: our drive to the Hurricane Ridge on a 9 percent grade highway, 5,200 ft. above sea level. As we headed toward the ridge, magnificent views of the snow-capped Mount Olympus, Mount Constance and other Olympic mountains, whose sides and ridgelines are topped with massive glaciers, appeared on the horizon.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ We walked on nature trails to get clear views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Vancouver Island in Canada, which we strained to see from Port Townsend the previous week. We also saw wild bear and elk roaming around the lodge.

[The Hanukkah Eve Windstorm of 2006 extensively damaged the Heart of OƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢the Hills Campground. It was reopened in June 2007.]

Although we had explored almost the entirety of the scenic U.S. 101 surrounding the ONP, our forays failed to encounter the mountain region of the park adequately.

Finally, back at the campgrounds, I took Carmel and Junius to the campfire program on ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-The geological changes in the Olympic Peninsula.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ After another day of driving some 170 miles, we deserved a good nightƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s sleep.

A view of Hurricane Ridge Trail at ONP (25 August 2007)

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Photo by Vranak.]

(Next: Exploring British Columbia)