The Devolution Debate: Facts that should not be forgotten

Posted on October 10th, 2017

Author: G. H. Peiris

Several articles by Dr Dayan Jayatilleke published in The Island during the past few days indicate that he is very definitely the most articulate and, arguably, the most “intermestic” exponent of the notion of the ’13th Amendment’ (implemented more comprehensively than at present with all powers and functions referred to in its Ninth Schedule vested on Provincial Councils – PCs) being the constitutional via media that would ensure stability, good governance and interethnic harmony. Dr DJ is no doubt aware that, following the misguided curtailment of Presidential powers through the 19th Amendment of the Constitution in 2015, alongside the practice of foreign agents including diplomatic personnel bypassing the Colombo government in their transactions with the ‘NorthernPC’ emerging an unofficial ‘convention’ in Sri Lanka’s external relations, his prescription would actually entail the creation of a more autonomous network of PCs than envisioned at the promulgation of the 13th Amendment thirty years ago.

The third instalment of Dr DJ’s recent discourse on this subject (The Island, 21 September) is adorned with the maxim “Fuggetaboutit” – borrowed from a display of machismo by a character in the Hollywood crime serial ‘Miami Vice’. Contextually the maxim is an initial thematic thrust intended to persuade the readership that the ‘Province verses District’ dispute should be forgotten about because “…it is no longer a legitimate subject for debate”. But thereafter he proceeds to argue passionately on the side of province-based devolution, implicitly equating all other viewpoints as representing the cardinal sin of ‘unilateralism’. In an attempt replete with oracular assertions (woefully deficient in hard evidence) intended to reinforce his own submissions to this “illegitimate” debate, he makes a passing reference to the wisdom of Gautama the Buddha and Aristotle the Hellenic sage, and then broadcasts a haphazard scatter of mundane pronouncements and prescriptions by others such as SWRD Bandaranaike’s “federal proposal” which was no more than a fledgling test-flight by a highly pedigreed young man in the late 1920s towards nationalist leadership; Joseph Stalin’s demented pronouncement on the existence of a “common culture” among the innumerable nationalities enslaved in the gigantic Russian Empire of his time; Fidel Castro’s supposedly profound thoughts on “healing the wounds” of unresolved ‘National Questions’ in Sri Lanka and, believe it or not, in the ‘African Horn’; JR Jayewardene’s disclosure to the Editor of ‘Lanka Guardian’ which the veteran journalist did not consider worthy of mention anywhere in that journal; and Vijaya Kumaratunga’s call (figuratively, no doubt) for “inter-communal marriage”. Quite hilarious – please re-read it and enjoy, unless you wish to “Fuggetaboutit”.

Following a brief interval thereafter The Island of 25 September carried what could well be Dr DJ’s first salvo at two of his critics in which there is an elaboration of his earlier reference to the well-known “Middle Path” enunciated in Buddha Dhamma, and a solemn exposition of the “Mervin Doctrine” (no toothless grins please, you old ‘College House’ fogies). Both these are intended to lead us along our maestro’s “Middle Path”, and to terrorise us with an apocalyptic spectre which any deviation from that path would ensue, specifically: “… ceaseless satyagrahas in the North and East …triggering a global media tsunami of denunciation, resulting in an Indo-US response against which China is too far away to defend us, should it be so inclined”. In responding to this exhibition of both multicultural erudition – a breath-taking range from Anguttara Nikaya to Peloponnesian Wars – as well as poignant filial devotion, should we, with all the gentility at our disposal, tiptoe away in respectful silence or, alternatively, shouldn’t we point out that the wisdom of remaining in the ‘Middle Path’, especially in political affairs, depends vitally on the destination to which the path leads and the nature of what lies beyond its lateral peripheries – i.e. the options? Shouldn’t we also whisper that even those with an elementary awareness of the history of our country do not need a sanctified “Mervin Doctrine” to appreciate, from contemporary geopolitical perspectives, the island’s locational hazards?

The late Mervin de Silva, we are aware, was a highly gifted journalists who (among other things) seldom lost his inimitable sense of humour, and an author of several erudite scholarly works on international affairs, especially of Southeast Asia – prescribed reading for a course I conducted in mid-career on ‘South and Southeast Asia’ at the University of Western Australia. Yet attempting, as Dr DJ has done, to underscore Sri Lanka’s geopolitical “helplessness” on the basis of what de Silva had written several decades ago, and highlight it as a criterion of decisive relevance to the current desultory but potentially disastrous exercises in constitutional reform is tantamount to a gross misrepresentation of the geopolitical transformations that have occurred in the Indo-Pacific Region since that time ̶ in particular, the emergence of China as a global superpower, and China’s increasingly formidable presence in the Indian Ocean maritime fringe and the Himalayan periphery of South Asia in the face of intense resentment especially on the part of the ephemeral Indo-US confluence of interests, and the salience of that transformation to the options available to Sri Lanka in the exercise of its rights of national self-determination.

In short, there is no need whatever to regard our country’s proximity to India as a karmic determinant that impels us to remain subservient to the constitutional demands made by (or backed by) the very forces – domestic and international – that had overtly or covertly nurtured the thirty-year Eelam War, and have persisted with their efforts to destabilize Sri Lanka after the battlefield defeat of the LTTE in 2009.

The last item in the list of extracts from the ‘Mervin Doctrine’ cited by Dr DJ states: “Through effective de-centralisation of power and resources devolved to Provincial Councils it may be possible to head off the next threat … the devolution of power should be matched by new economic growth areas“. In my view the relevance to this extract to the present debate stems mainly from the fact that even in Mervin de Silva’s capricious mind there was a distinct reservation regarding the capacity of province-based devolution to counteract the “next threat” (which presumably he perceived as a Delhi-led territorial dismemberment of Sri Lanka). Remember, this segment of his foresight was offered in 1993 by which time the ‘North-East Province’ ̶ a territorial entity of ‘regional’, rather than ‘provincial’ devolution based on the myth of an “exclusive, traditional, Tamil homeland” in Sri Lanka, epitomised in the LTTE banner and/or a component of a future state in the Indian federation no doubt as desired by Delhi. Further, despite the fiasco of unilateral declaration of independence by the elected Chief Minister, Vardaraja Peruma, of its short-lived PC, (no joke if a similar stunt is performed now – US, UK and India will probably rush to recognise Eelam as a ‘sovereign nation’) it had become more or less a permanent fixture, and remained as such for almost twenty years until a group of eminent lawyers persuaded the Supreme Court that its continued existence was unconstitutional. Mervin De Silva’s reservation appears to indicate that he was conscious of the risk which the devolutionary arrangement of the ’13th A’ entailed.

There was another doyen of comparable eminence in his profession, the late H. L. de Silva, whose perception of that risk is succinctly presented in the following passage (Sri Lanka: A Nation in Conflict – Threat to sovereignty, territorial integrity, democratic governance and peace, 2008): p. 122.)

“While being cognizant of the dangers of federalism in a political soil conducive to separatism it must not be assumed that there are no dangers in the grant of over generous measure of autonomy to peripheral units under a system of devolution, because devolution can in the long run contribute to the upsurge of centrifugal forces that eventually lead to secession and the breakup of the State. The introduction of devolution in the context of a political ethos that is prone to separatism must not be embarked upon recklessly without due care and caution.

That these nuggets of wisdom from the two De Silvas do not represent either ‘unilateralism’ from an ‘intermestic’ perspective or a rejection of devolution as a modality of power-sharing from ‘domestic’ perspectives is made evident by another fragment of the ‘Mervin Doctrine’ which Dr DJ has not cited verbatim but has glossed over with a hazy comment. That reads as follows: “Does this (the aforementioned locational adjacency to India) mean that a small nation must necessarily be subservient to its big neighbour, that it cannot pursue a policy independent of its big neighbour, or even hostile to its neighbour? Not at all. It can. But it must recognize and be ready to face the consequences of such a hostile relationship. We have a perfect example in Cuba, with whom we can draw parallels“ (see, Colombo Telegraph of 23 June 2013). In my own chinthanaya, the much maligned Pakistan has also accomplished that against all odds for seven decades vis-à-vis its Kashmir policy (despite losing its absurd “Eastern Wing” in 1971), abandoning the US-led SEATO before it became defunct since 1977, and consolidating its strategic links beyond the mighty Karakorum Range. That Mahinda Rajapaksa achieved for Sri Lanka the “impossible” of liberating the ‘Northeast’ must also be placed at a similar plane.

Repeating the multifaceted case against adopting a Province-based devolution as provided for in the ’13thA’ has been so persuasively presented from diverse viewpoints by many erudite critics over several decades makes it unnecessary for me to embark on yet another of its reiteration here. What I think is more productive is to focus on certain prevailing misconceptions on the merits of district-based devolution, but subject to an overarching qualification based on my personal conviction that a tiny nation like Sri Lanka does not need a second tier of sub-national institutions of government between the Centre and the network of Local Government Institutions (the latter described in Ursula Hicks’ classic, Development from Below, as one of the best of its kind in the Less Developed Countries) in order to rectify prevailing deficiencies from perspectives of the ideals of consociational democracy and social justice. I am encouraged to make such an attempt as briefly as possible because of the faint silver-lining I see in the recent instalments of Dr DJ’s discourse – stemming ironically from his sustained campaign for the ‘Province’, resorting to patently absurd pronouncements such as: “The Steering Committee report also puts paid to the debate on the unit of devolution” and, implicitly an indication that there still remains an effort to revive the ‘District case’ which he finds it necessary to crush. I also have reason to wonder whether his incessant flow of wisdom during the past fortnight on the ‘Province vs. District’ issue is also aimed at suggesting to his readers that at least some of the eminent personalities who shared with him the recent ‘Eliya’ platform also share his views on a ’13thA plus’ reform. Or, is he trying to signal to the Yahalapana leaders that he really means no harm.

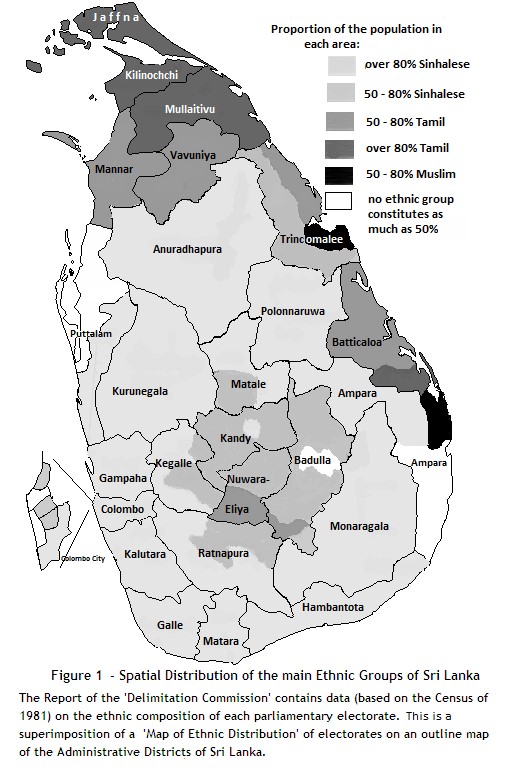

One of the most obvious merits of the District as the spatial unit of devolution is that it would serve as a far more effective system of facilitating the objectives of devolution than the Province in the context of the present spatial pattern of ethnicity in the island (as depicted in Figure 1). In this context what is of paramount relevance is that the majority of

|

Tamils and Muslims in Sri Lanka live outside the ‘North-East’; and since dispersal of political power is meant for the people rather than territory, devolution to provinces cannot result in a change in political entitlements of the majority in these two communities. The transfer of political power to Districts, on the other hand, has the potential of genuine political empowerment of a much larger share of their respective populations. Since such empowerment at district-level will not be seen as a serious threat to the territorial integrity of the nation, the need for overarching central control of the devolved powers and functions of district governments will be substantially reduced. Such an arrangement will also provide scope for an institutionalisation of effective inter-ethnic power-sharing at the Centre. In this sense, it is the District, rather than the Province that epitomises the ‘middle-path’ between total abandonment of devolution to a sub-national network of intermediate institutions, and a further reinforcement of devolution in accordance with the ’13th A’ with the risks and uncertainties it entails.

A reform involving untrammelled devolution of all powers and functions on the provinces envisaged in the ’13th A’, quite apart from its probable effect of strengthening the centrifugal forces that have continued to pose a challenge to territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, will, in addition, result in total chaos in respect of the functions of government pertaining to ‘Law and Order’, and ‘Land and Land Settlement’ as stipulated in two of the Appendices attached to the ‘Provincial Council List’. The glib advocacy of the ’13thA’ without reference to this fact is, indeed, beyond the realm of sanity, for the reason that exact specification of the powers and functions to be devolved ought to be considered the foremost determinant of the spatial framework of a devolution. A careful study of the dispensations on ‘Law and Order’ and ‘Land and Land Settlement’ as stipulated in the Government Gazette of 20 November 1987 (pages 23 to 32), for instance, suggests that the Steering Committee had not even bothered to look at those segments of the ’13th A’, leave alone consider their implications and impact to the contemporary political realities in our country.

A sane reader of the section titled ‘Law and Order’ will undoubtedly see that, in the context of province-based devolution, some of the most arduous tasks such as preventive action against politicised mob violence in Metropolitan Colombo and its substantially urbanised hinterland, or the conduct of operations against organised crime in its spatially hazy underworld the tentacles of which extend from the metropolis well into rural areas in all parts of the island, will encounter bewildering confusions, especially in respect of coordination, chains of command and accountability, under the fragmentation of police manpower, functions and operational areas of authority. It also does not require expertise on this subject to realise the chaos that would ensue in the maintenance of law and order specially in unit such as the Eastern Province stretching as it does from Kokkilai to Kumana over a linear distance of some 180 miles, or the Northern Province, covering about 14% of the total area of the island, much of it providing forested hideouts for subversives and criminals, and fully exposed to irredentist infiltrations, being policed by a hierarchical structure headed by a DIG appointed to that post with the concurrence of a Chief Minister (who could be even more unreliable than the one we have at present), but accountable to both to a Colombo-based IGP, a national Police Commission and an Executive President in a ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ (but enjoy the perks of evil) mode. There is reason to speculate that in such a system the maintenance of law and order especially in the North and the East is likely to replicate that of several parts of the ‘Red Corridor’ of India stretching across the Deccan where, as studies conducted by scholars like Ajay Mehra on ‘People’s War Groups’ (a.k.a. ‘Naxalites’) indicate, there are well over 150 Districts out of India’s total of some 700 into which formal government penetrates only in the form of occasional paramilitary operations. Delhi’s ‘South Block’ bureaucrats who made it possible for the Parathasarathys, Bhandaris, Chidambarans, Venkateshwarans and Dixits to disregard, often with contempt, the submissions of their Sri Lankan counterparts like ACS Hameed, Gamini Dissanayake and Lalith Athulathmudali at negotiation forums probably wanted to create that kind of chaos in Sri Lanka.

The related landmark episodes were, first, JRJ’s conciliatory meeting with a less-than-cordial Indira Gandhi and the discussions he had with the aggressive diplomat Parathasarathy in November 1983 who, it is said, insisted on the Sri Lanka president abandoning his ‘District Development Councils’ scheme come what may. The tangible outcome of that encounter was the so-called ‘Annexure C’ which engraved the ‘Province’ as the TULF bottom-line for negotiation on ‘Land Powers’.

This happened, it should be recalled, in the aftermath of JRJ’s ‘Referendum’ blunder of December 1982 which, among other things, paved the way for a distinct anti-UNP transformation of electoral morphology, and the early signs of an economic downturn. More importantly, it happened in the all-pervading gloom of the ‘1983 Black July’ of when it was known to those in Colombo’s corridors of power that certain TULF leaders were prodding Delhi to undertake a Bangladesh-type military intervention in Sri Lanka to “liberate” the island’s ‘Northeast’ ̶ a distinct Indira Gandhi option kept in storage until the suppression of the Khalistan challenge through her massive ‘Operation Blue Star’ of June 1984.

Thus, with Rajiv Gandhi succeeding his assassinated mother events moved swiftly. There was the ‘Delhi Accord’ of August 1985, followed by many other Indian intrusions intended to enforce the Indian will on the working out of the details of the Accord, with scant regard to the usual diplomatic niceties meant. The ‘Political Parties Conference’ of April 1986 summoned by our lame-duck president in desperation about the intensifying tempo of insurrectionary violence in both the ‘North-East’ as well as the ‘South’, the participation in which was confined to the TULF leaders whose “boys” had already up-staged them as representatives of the northern Tamils (and probably earmarked them for future liquidation), and a few worthies of the “Old Left” whose trade-union base was virtually non-existent. The rejuvenated SLFP led a massive campaign of protest. The key leaders of the Muslim community remained noncommittal. Even stalwarts in the ranks of the ruling party like Premadasa, Athulathmudali, Gamini Dissanayake, Gamini Jayasuriya, Ranjit Atapattu and HM Mohammed either maintained low profile with some among them making no secret of their opposition. There was then the shocking Indian air-borne military intervention staged to foil the ‘Operation Liberation’ staged in Vadamarachchi in June 1987 – to JRJ, a shattering indication that affable Rajiv had not abandoned Indira’s policy of supporting secessionism in Sri Lanka.

This is really how the infamous ‘Rajiv-JRJ Accord’ and the cancerous Provincial Council system was implanted. Having heard certain details from a few ex-Peradeniya officials who had to painfully witness these “negotiations” (one of my graduate students along with three in his support staff were incarcerated for aiding an attempt to forestall, as requested by Gamini Dissanayake, from ‘Annexure C’ specifications on land settlement under the Mahaveli Programme) I just cannot “Fuggetaboutit” – no way.

The fallacy of the notion that the Provincial Council system (with a supposedly interim merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces) was the outcome of an indigenous evolutionary process of compromise and consensus in mainstream politics could be grasped from the following portrayal by another illustrious De Silva – Professor K. M., a close and loyal associate of JRJ – of the ethos at the formalisation of this pernicious Accord on 29th July 1987.

“Even as the cabinet met on 27 July violence broke out in Colombo when the police broke up an opposition rally in one of the most crowded parts of the city. It soon spread into the suburbs and the main towns of the southwest of the island and developed into the worst anti-government riot in the island’s post-independence history… When Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi arrived in the island on 29 July to sign the accord the security services and the police were still engaged in preventing the mobs from entering the city of Colombo intent on demonstrating their opposition to the accord. The situation in the country was very volatile at the time of signing of the accord, with news coming in of a dangerous mob making its way to Colombo on the Galle road through Moratuwa and the Dehiwala Bridge. There was every possibility that the government would have been overthrown and JR himself deposed. That explains why a request was made for Indian army personnel to take over from the Sri Lanka army in Jaffna; and above all, the sending of two Indian frigates to remain outside the Colombo harbour – placed very conspicuously – as a token of Indian commitment to protect the government, and available to evacuate JR and those who supported the accord just in case it became necessary to do so”.

In order to refute another fallacy that has even greater significance to current Sri Lankan constitutional affairs, I should draw the readers’ attention to the fact that Rajiv’s peace efforts, featured as they were by an ostentatious pretence of moving away from his late mother’s aggressively ‘imperious’ approach to dissention between Delhi and its peripheries both internal as well as external, entailed the signing of several ‘peace accords’ that turned out to be short-lived; and, contrary to what some of our pundits would like to make us believe, the Accord of 1987 does not have the status of an inviolable treaty of the type enforced by the victor on the vanquished in wars the world has witnessed over several centuries and that, in any event, it was India that failed to fulfil its Accord commitment to Sri Lanka and make it null and void.

If the Steering Committee has proposed the en bloc adoption of the ”13th A (why this is yet to be clarified through an official announcement is typical of the absurdly surreptitious constitutional reform procedures), it indicates a perfunctory approach towards its task. First of all, ‘Appendix II of the ‘Ninth Schedule’ titled ‘Land and Land Settlement’ makes it abundantly clear that the real architects of the ’13thA’ (bureaucrats of Delhi’s South Block) had a prejudiced and excessively narrow, perception of what powers and functions over ‘Land’ in Sri Lanka really entails. In confining their stipulations almost entirely to the distribution of state land among the rural poor, they appear to have been guided by: (a) the thoroughly discredited notion of the Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka constituting an exclusive ‘Traditional Tamil Homeland’, (b) a belief inculcated by the TULF of land settlement (the foremost development strategy in Sri Lanka from about the mid-1930s) being a government-sponsored process of Sinhalese encroachment of that homeland, and (c) a ready acceptance of the grievance of the TULF leadership that the ongoing Mahaveli Development Programme (MDP) will accelerate that ‘encroachment’, in disregard of the fact that ‘downstream’ agrarian development in areas earmarked by the ‘Mahaveli Authority’ for settlers selected from the Tamil and Muslim peasantry was being prevented by their own “boys”. Thus, in their haste to work out a response to the TULF demand on ‘land powers’ in the hope that Tamil terrorist groups could thus be appeased, they also overlooked the fact that the term ‘land’ is definitionally hazy and that the related constitutional specifications should encompass a wide spectrum of powers and functions of government stretching in their applicability from an international plane (as witnessed at the ‘nationalisation’ of plantations in 1975 and expected for the inflow of foreign investment in the ‘Singapore Model’ of the open economy), at the one extreme, to that of the individual citizen (as experienced in the employment of the Land Acquisition Act of 1950 or the Land Reform Law of 1972), at the other. They also paid scant regard to the fact that a fragmentation of authority over land could constitute could result in a political cum administrative mess for large-scale inter-provincial development projects such as the ‘Gal Oya Scheme’ of early independence and the ‘Mahaveli Development Programme’. The considerations stemming from these deficiencies of the ‘Appendix II’ appear to have been of no consequence to the relevant sub-committee (disgustingly including JO representation as well) or the pretended ‘constitutional law’ expertise that has gone into the compilation (as the snippets of information available to us) the Steering Committee Report. That is nothing compared to the shock of reading a national newspaper report on 30 September according to which the President of the Republic had not seen the Steering Committee Report supposedly submitted to parliament ten days earlier.

The other considerations pertaining to ‘Land Powers’ that ought to have been accorded careful consideration in the compilation of the Steering Committee report are (to state as briefly as possible) are: (a) that development programmes in Sri Lanka involving the harnessing of ecological resources of large areas such as the MDP and the earlier ‘Gal Oya Scheme’ were implemented under special statutory ‘Authorities’ vested with administrative powers that transgressed provincial and district boundaries; (b) that ‘Land’ powers should be designed to embrace a wide range of vital governmental concerns such as environmental conservation, solid waste disposal and control of atmospheric and hydraulic pollution, counteracting natural hazards including the impact of global warming that would result in acute regional water deficiencies and, as Chandre Dharmawardena with his impeccable expertise has explained in a recent issue of The Island, territorial losses along the island’s maritime fringe; (c) that, as C. M. Madduma Bandara, encapsulating long years of invaluable environmental research and his experience as the Chairman of a Land Commission of the late-1980s has insisted in several publications, the present provincial delimitation, a remnant of colonial administration finalised in 1898 designed mainly to set the stage for an explosive growth plantation enterprise in tea and rubber, is totally inappropriate from the viewpoint of contemporary land-based resource utilisation.

More generally the fact that Delhi’s bureaucrats who prepared the ‘position papers’ for the Indian ‘foreign affairs’ stalwarts who were engaged in Sri Lanka “negotiations” during that fateful episode paid scant regard to these considerations is no cause for surprise. The real surprise is that the present ‘Steering Committee’ appears to have remained oblivious to the sordid thirty-year record of Provincial Councils which indicates more than all else that, while their custodians have spared no pains in personal empowerment and aggrandisement, they have failed to make optimum use of the resources placed at their disposal by the Centre, had many lapses even in routine functions such as salary payments to their employees, created bloated administrative structures, intensified local-level electoral malpractices and at least sporadically contributed to the proliferation of politicised crime and, barring a very few exceptions, accomplished nothing for the benefit of the people that couldn’t have been done more efficiently and economically by agencies of the central government with due regard to prioritising the survival of Sri Lanka.

G.H. Peiris is Professor Emeritus of the University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka

His recent research writings include Twilight of the Tigers (OUP, 2009), Political Conflict in South Asia (University of Peradeniya, 2014) and Sri Lanka: Land Policy for Sustainable Development (Visidunu, 2017) and Contemporary Buddhist-Muslim Relations in Sri Lanka, e-publication in Thuppahi and Lankaweb (2017).