Adaptation and sustainability integral to ancient civilization

Posted on December 24th, 2021

By Seneka Abeyratne Courtesy The Island

Ruminations on Sri Lanka’s Ancient Past – Part VI

The evidence assembled by C.R. Panabokke, in ‘Evolution of the Indigenous Village Irrigation Systems of Sri Lanka’ (2010), shows the transition from rainfed to irrigated agriculture took place mainly in the 3rd century BCE. A study by Rukshan Jayawardena, ‘Ancient Irrigation and Related Settlements of the Early Historic Period’ (1997) yields useful information on the growth of irrigated agriculture during this period. There is no reliable evidence to indicate that rice was grown on the island during the ‘pre-Vijayan’ period. First came the village tank. Then came ‘irrigated’ rice cultivation in the field below the tank. By the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, the village tank had become an integral feature of the undulating terrain of the dry zone (Nicholas, C.W. History of Ceylon, Vol. 1, 1959).

Low-humic gleys

As in the past the soils now used for rice cultivation are mainly the poorly-drained low-humic gleys (LHGs), which occupy the valley bottoms and can be puddled. Since the well-drained reddish brown earths (RBEs), which occupy the mid and upper slopes of the dry zone landscape, cannot be puddled like the LHGs, they are unsuited to rice cultivation. In Sri Lanka the valley bottoms are called lowlands, whereas the mid and upper slopes of the undulating topography are called uplands. There is no hard evidence of rice having been grown under rainfed conditions in the dry zone uplands (RBEs) in the protohistoric period.

The evolution and spread of small village irrigation systems in Sri Lanka could be viewed as an internal development that occurred over a long period of time in response to the distinctive agro-ecological features of the dry zone, which were by no means uniform. As noted above, it was the lack of any form of shallow groundwater that necessitated the surface storage of water in the north-central dry zone – the cradle of civilization in Sri Lanka.

A typical village in the NCP consists of the village tank and a paddy field below it. Many experts, including Panabokke, have stated that without artificial storage of water, human existence in the NCP would have been impossible. The village tank provided water for multiple uses during the prolonged dry season, including agriculture. It enabled farmers to combine cultivation of kurakkan, gingelly and other seasonal food crops in the ‘rainfed’ uplands during the Maha season with rice cultivation in the ‘irrigated’ lowlands during the Yala season. This was a major technological breakthrough that greatly enhanced the food production potential of the north-central dry zone in the 3rd century BCE.

Nuwan Abeywardana, R.L. Brohier, R.A.L.H. Gunawardana, R.W. Levers, Rukshan Jayawardena, Madduma Bandara, C.W. Nicholas, C.R. Panabokke, Henry Parker, A.M.P. Senanayake, Sudharshana Seneviratne, M.U.A. Tennakoon, and many others, through their scholarly research, have deepened our understanding of how and why the tank village emerged as the basic unit of settlement in the dry zone in ancient times. Even today, these settlements dotting the hard rock basement terrain of the dry zone continue to play a vital role in preserving its economic integrity and cultural identity. A recent study indicates there are about 10,000 functional village tanks originating from the ancient water-harvesting system in the island (Abeywardana, Nuwan; Bebermeier, Wiebke; and Schutt, Brigitta, Ancient Water Management and Governance until Abandonment, and the Influence of Colonial Politics during Reclamation, 2018).

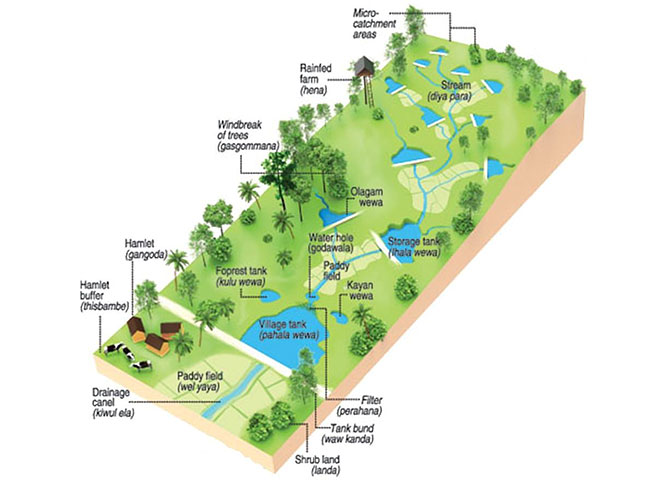

Tank Cascade System

A tank cascade system could be defined as a chain of small tanks organized within a micro-catchment of the dry zone in Sri Lanka. The tanks in the upper catchment store water from a seasonal stream and convey it to other tanks downstream. The village tank is the lynchpin as it collects water from all the other tanks in the cascade system. The water stored in this manner is used for agriculture as well as other community activities. The proper functioning of the village tank therefore depends critically on the condition of all the other interconnected tanks which drain into it. When they fall into a state of disrepair, the system breaks down.

The number of cascade systems varies significantly from one river basin to another. For example, the Mee Oya river basin has only one associated cascade system. The Malwathu Oya river basin, on the other hand, has 179 associated cascade systems (IUCN Sri Lanka, , 2016). High priority should be given to ensuring the sustainability of the village tank settlements as they have been the backbone of civilization in the dry zone since the 3rd century BCE. Most of the entrenched problems pertaining to management and organization of small tanks identified in a report by Saleha Begum (Minor Tank Water Management in the Dry Zone of Sri Lanka, 1987) continue to remain unresolved.

The narrow inland valley systems carved out on the basement rock terrain is a distinctive feature of the areas comprising Sri Lanka’s dry zone, especially the North-central and North-western provinces. The small tank cascade system is found mainly in these regions, where the undulating landscape is crisscrossed by these inland valleys. This is a good example of the skill-level reached by the local ‘scientific’ community in such areas, in the form of irrigation engineering, soil and water management, and agronomy in the 3rd century BCE.

It is important to note that this development did not occur suddenly; rather, it was an ‘evolutionary’ process that occurred over a long period of time. A key feature of this process is that it produced the kinds of innovations that were suited to the various environmental conditions in the dry zone. Clearly, adaptation and sustainable development were concepts that were not only well understood but also practiced by the pioneers of small-scale irrigation and water management in Sri Lanka.

Due to the sustainable management structure set up within society, the small tank systems existed intact for more than two millennia…Different layers of management strategies were implemented, blending centralized larger irrigation schemes with locally controlled small irrigation systems. Buddhist temporalities were used to link the hinterland with the main settlements…” (Abeywardana et al, 2018).

Tamil Nadu also boasts of a modest small-tank cascade system, but whether it borrowed the technology from Sri Lanka or vice versa is not clear. An overview of this system is provided in a report by Krishnaveni, M.; Sankari, Siva; and Rajeswari A. (Rehabilitation of Irrigation Tank Cascade System Using Remote Sensing GIS and GPS, 2011). The physical and cultural landscape of Sri Lanka differs significantly from that of Tamil Nadu. Hence, in terms of future research, a study that compares the historical evolution and organizational structure of the tank cascade systems in these two regions would be a useful activity to undertake.

Caption Pic 1:

Tank cascade system. (Image courtesy: Paranage, K. [2018]. ‘Understanding the Relationship between Water Infrastructure and Socio-Political Configurations: A Case Study from Sri Lanka’)