Travels of a journalist [2013 Series #3] Weligama Podda tours his native South in the guise of a global citizen

Posted on June 2nd, 2013

By Shelton Gunaratne, author of From Village Boy to Global Citizen, Vol. 1: The Journey of a Journalist; and Vol. 2: The Travels of a Journalist (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris).

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-ThereƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s no place like homeƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ is the last line of the 1822 song ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Home Sweet HomeƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ written by John Howard Payne. From music, the phrase passed onto drama and books as well.

The phrase inspired me to create my 2012 book Village Life in the Forties (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse), a collection of autobiographical sketches highlighting my experiences in the village of Pathegama, which I still consider to be my ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-homeƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ even though I left Sri Lanka at the age of 26 to live overseas.

Thus, I gave top priority to re-visiting Pathegama during my 2013 island wide excursion. I wanted to re-connect with the entire Southern Province comprising 2.3 million people living in an area of 5,559 square kilometers. We decided to spend one day exploring the coastal area of the Galle District, and another day imposing ourselves on our relatives in the Matara District. Then, we would hurry through the Hambantota District all the way to Tissamaharama to spend the third night.

Our driver, Amal Chandrakumara, picked us up in Negombo Sunday morning for a lecture in Colombo. Early afternoon, we proceeded on our journey along the 128 km Southern Expressway, the countryƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s first freeway, which has slashed travel time between Colombo and Matara to a mere 1.5 hours. I was disappointed that the expressway rest stops were commercial ventures that required money even to use the ground-floor toilet facilities unlike the Minnesota rest areas on Interstate 94, which provide travelers with picnic tables, walking paths, free toilets, etc.

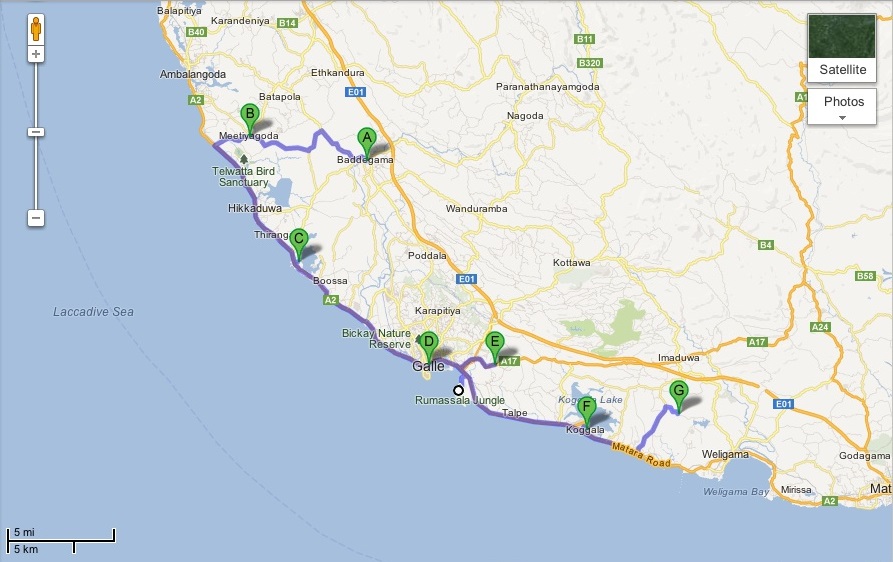

We left the expressway at Exit 7 (the Baddegama Interchange), 103 km from Colombo, because our driver was keen to show us the moonstone mining operation in Meetiyagoda, near Hikkaduwa. Moonshine is a feldspar that has a special shine that resembles the moonƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s. The mineƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s sales folk couldnƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢t persuade us to buy any moonstones but they succeeded in selling us a packet of peeled cinnamon for Rs. 200. The mine was only 2.5 km away from the site of the worldƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s worst railway disaster that killed 2,000 people when the Boxing Day tsunami of 2004 overturned a crowded train.

Then, we drove southeast on the coastal road to Galle witnessing the damage the 2004 undersea megathrust earthquake had inflicted on the tourist town of Hikkaduwa renowned for its surfing and snorkeling facilities. We saw the new housing schemes that various philanthropic organizations had built to settle down the survivors of the fisher folk devoured by the 30-meter high waves of the Indian Ocean energized by a powerful undersea earthquake epicentered in the Indonesian waters more than a thousand kilometers away.

Although Galle (pop. ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ 112,252) was our destination for the day, we drove an extra 10 km further east on the Imaduwa Road to the village of Happawana, where my older sister Rani ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ used to live.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ On my excursions to Sri Lanka in the 1990s, I used her home named ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Somagiri,ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ located on a hillock, as my operational headquarters.

Rani and her husband left ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-SomagiriƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ to live in a new house they built in Kurunegala, the city that we planned to visit at the end of our island wide tour.

Because both Yoke-Sim and I had stayed in ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-SomagiriƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ a few times, we had nostalgic reasons to re-visit it to see its current condition. But we had difficulty locating the property because, as our inquiries revealed, the neighbor in a land dispute had closed the path to ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Somagiri,ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ the once majestic hilltop bungalow. Sudu Mahattaya had to hire a tuk-tuk to transport us to the hilltop through a makeshift footpath.

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-SomagiriƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ was now in shambles.ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ The occupants had turned the colonial style verandah into a storehouse for paddy. Signs of gloom and doom depressed us, but we joined the couple for evening tea. Knowing full well that the couple was financially down and out, we gave them a financial gift before we returned to Galle to check in at Frangipani Motel on Pedlar Street in the fort.

I have already recounted my Happawana exploits in Chapter 18 of the first volume of my autobiography subtitled The Journey of a Journalist (Xlibris, 2012). I recalled the role of Mahadenamutta I played in evening discussions with the cream of the Happawana intellectualsƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚Gunapala, the village political analyst; and Siripala (aka Sathya Dayaratne), the novelist. Only Wickremasinghe, the schoolmaster, made it to see me on this short stopover.

Inasmuch as I was a literature buff in my early years, it occurred to me that the Southern Province was the birthplace of three of my favorite writersƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚Jinadasa Vijayatunga (1903-1989), the author of Grass for My Feet; Gunadasa Amarasekera (born in 1929), the author of Karumakkarayo; and Martin Wickremasinghe (1890-1976), the author of Gamperaliya. Amarasekera was born in Yatalamatta, just five km north of Urala, where Vijayatunga was born. These two villages lay along the Wanduramba Road northwest of the Pinnaduwa Interchange of the Southern Expressway.

Malalgama, the birthplace of Wickremasinghe, lay close to the coastal highway in Koggala, about 15 km east of Galle. I found immeasurable satisfaction in reading most of his masterpieces. I was proud to imitate the Wickremasinghe style when I submitted assignments to the Sinhala Literature class that D. B. Kuruppu taught at Ananda College. ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ My birth village of Pathegama was only 12 km northeast of Malalgama.

We decided to focus on Koggala and Pathegama most of Monday. Although we had been to Galle many times before, we did not know much about the Galle Fort (also called the ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Ramparts of GalleƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚), which the Portuguese built in 1588 and the Dutch extensively fortified from 1649 onwards. Therefore, we took up AmalƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s suggestion to admire and explore this exceptionally well-maintained World Heritage site, which withstood the force of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami. The posh Amangalla resort hotel, originally built in 1684 to house the Dutch governor and his retinue, is an outstanding part of the fort complex.

Galle, the islandƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s third largest municipality, has developed around the Galle Fort area, which covers 52 hectares (about 130ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚ acres) of the city area of 1,650 hectares. In 1663, the Dutch added some 14 bastions built of coral and granite to strengthen the fort, which now looked like a small laid out walled city with a rectangular grid pattern of streets full of the Dutch colonial style low houses with gables and verandahs. Our walk on the walls of the fort brought memories of my visits to the walled cities of Chester and York (in England), and Xian (in China). The well laid out road network and the many historical buildings of the fort impressed us. The cultural diversity of the fort residentsƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚Sinhalese, Moors, Tamils, Europeans, and othersƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚was another feature of the fort.

After eating our breakfast at a popular pastry shop in Galle, we drove east on the coastal highway, past the suburb of UnawatunaƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚well known for its Jungle Beach, Peace Pagoda, and the Rumassala MountainƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚to Koggala, the site of the Martin Wickremasinghe Museum of Folk Culture complex.

I had already visited this complex in the early 1990s when I was vacationing in Happawana. Because the man in the ticket booth agreed that a native of a neighboring village should not be treated as a foreigner, he charged me only Rs. 20 whereas Yoke-Sim had to pay an admission fee of Rs. 200.

The museum complex has an ecosystem implanted to reflect a multitude of the indigenous trees and shrubs, as well as the bird life it attracts, that Wickremasinghe mentions in his writings. It is a remarkable attempt to recreate the novelistƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s homestead in Malalgama. His ashes lie in the mound on the right flank of the house. The Hall of Life exhibits many of his memorabilia and tells his life story through a plethora of photographs, awards and souvenirs.

Since the museumƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s opening in 1981, it has expanded itself to accommodate many artifacts of Sri Lankan folk culture from ancient to modern times, including those related to rural technology and religious ceremonies. I was privileged to donate a complimentary copy of my book Village Life in the Forties to the museumƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s exhibition of the works of southern writers.

[Courtesy: Sunday Times]