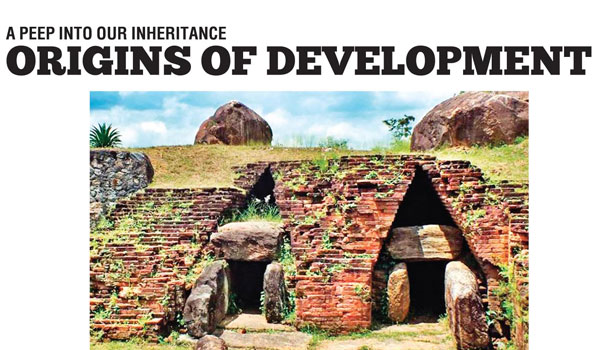

A Peep into our inheritance – Origins of Development of Ceylon

Posted on September 2nd, 2016

By Dr. Tilak S. Fernando

We are being reminded today in the 21st Century how ‘good old Ceylon’ had been a self-sufficient island many eras ago. It also makes us wonder, with the present generation with scholars, professors and eminent engineers and so forth, why such inherited Sri Lankan talents from our forefathers’ time and the old civilizations have been allowed to take a reverse turn over the centuries!

Our forefathers had no proper transport systems at all to start with to carry heavy goods by overland to far-away destinations. In fact, such long haul was never heard of! This very fact or the people not having had the choice made them compelled to cultivate vegetables, fruits and other produce for their own consumption and needs, which helped in their survival at village level. Such actions naturally gave them the incentive and enabled farmers to cultivate paddy fields to enhance the social and economic needs of the country as a whole.

Paddy cultivation

At the commencement, paddy cultivation was two fold. Farmers at first had to clear out the jungles and prepare the fields for agriculture, and then they became hundred per cent dependent on rain for water. Once the muddy fields were ready to germinate seeds, paddy cultivation started and continued at every season (kanna).

In the second process, properly constructed irrigation systems helped the farmers with paddy agronomy. Had the next generation of farmers followed suit and tried to emulate their great grand ancestors’ methods and techniques, it would have been much easier to make a complete success of paddy cultivation; a lucrative agri business and a justifiable and profitable vocation.

Royal Property

According to old concepts, the king of the land became the sole owner of every inch of land. Every citizen who managed to get an allocation of land from the king had to pay a particular form of tax to the royal household according to the type of service one rendered to the king.

The king’s subjects generally paid ‘income tax’ out of selling their produce obtained after cultivating the lands allocated to them by the king. As a matter of fact, the monarch had no fixed income, salary or a ‘treasury allocation’ as such his whole income depended on tax collected from every plot of ‘royal land.’

To perform this task quite professionally and effectively and to ensure that the king received his fair share from his subjects a ‘courtyard’ (treasury) maintained a concise dossier of records with finite details of ownership of paddy fields and the expected output from those at every kanna. In this regard the King’s entitlements were marked in a special register called “Lakam Mitiya”. This method helped the King to have all the details at his fingertips, which acted as a comprehensive survey with statistics of the stock levels of rice produced, including the total number of farmers. To conduct a smooth operation in the way the king wanted all officials, including that of Vidanes were subjected to rigid royal command.

Another important aspect of the King’s governance was that all farmers had to share a common factor, which meant, the supply of water or irrigation to every paddy field had to be shared by mutual agreement and not by force. During this epoch people enjoyed the freedom to coordinate and help themselves in building small waterways, ponds and lakes, but massive projects had to be constructed with the king’s assistance and approval. At times certain areas and fields had been allocated by the royal approbation for various types of cultivation. It is therefore clear that there existed a systematic and methodical forward planning when it came to cultivating different kinds of provisions.

A study of the ancient irrigation systems adopted in the bygone era reveals about the professional approach adopted by expert planners, engineers and designers at that time.The present generation has access to observe and update themselves about the by-products of such intricate engineering with their own naked eyes, even today. It would undoubtedly help them to emulate such proficiency and benefit out of such observations when it comes to colossal projects of similar nature for the benefit of our future generations. The boundless talents of our forefathers have been observed and appreciated by foreigners who have had the opportunity to witness such ingenious operations and have idolised and adulated such masterpieces in the following manner.

Ancients

In approximately 1910, an American traveller by the name of Bigelow believed that despite the clear advantages the modern civilizations possessed with regard to technology, the ‘ancients,’ particularly the Egyptians, possessed a number of innovations that even 19th Century ingenuity could not rival. During his visit to Ceylon he had this much to say:

” Today Europeans are bewildered when they come into contact with some of the innovations the Aryans had come out with many centuries ago, even very much prior to the civilizations of the west took place. I have to admit that it is astonishing when one looks at the irrigation industry in Ceylon where they had adopted ingenious methods of building reservoirs, water holes simply to supply water to their cultivations. When one considers the Ceylonese engineers’ ingenuity and creativity and try to compare our imaginative work done at Panama Canal, it can only be compared as child’s play…”

Ceylon had been a colony under the British Empire for one and a half centuries. When looking back at our own backyard there is sufficient proof to say how we have been instrumental in turning our country into a ‘miniature Britain’ during this era.

In the foremost reports on irrigation published by the order of the Ceylon Government in 1855, John Bailey, Assistant Government Agent of the Badulla District, has recorded thus:

“It is possible, that in no other part of the world are there to be found within the same space, the remains of so many works of irrigation, which are, at the same time, of such great antiquity, and of such vast magnitude, as in Ceylon.”

Sir Emerson Tennant, the British Colonial Secretary to the Government of Ceylon, (1845-49) and author of many books on Ceylon observed:

“The stupendous ruins of the reservoirs are the proudest monuments which remain of the former greatness of the country.”

Governor Sir Henry Ward (1855-1860), whose intense personal interest in the ancient irrigation system of Ceylon, made him declare:

“There can be no doubt that the run of water is regulated by one of those ancient sluices, placed under the bed of the lake, which seemed to have answered so admirably the purpose for which they were constructed, though modern engineers cannot explain their action”!

Sir Henry Parker, an English engineer, whose duties permitted him to gain an intimate acquaintance with the ancient works said:

“I have never concealed my admiration of the engineering knowledge of the designers of the great irrigation schemes of Ceylon and the skills with which they constructed the works.”

- L. Brohier, author of The Story of Water Management in Sri Lanka down the Ages, quotes instances where the Sinhalese engineers were commended by other countries for their engineering feats.

Recent investigations have revealed that the methodology and the know-how used by our ancestors in irrigation work were equal and on par with that of the modern techniques. When Sri Lanka embarked on the mammoth Mahaveli Irrigation Project in the 20th Century, modern professionals using the latest technology were researching where to establish the Maduru Oya sluice gate when they miraculously managed to unearth the very ancient sluice gate which is supposed have belonged to the Anuradhapura – Polonnaruwa era!

In the ancient past the conventional gradient levels for water to flow from main reservoirs had been one inch per mile, and at times even up to six inches! This goes to show how competent and proficient our ancestors had been.

Our forefathers had never been dependent on rain alone for water for their cultivation, instead had gone hammer and tong in exploring new ways to divert water from lagoons and basins by constructing river embankments and causeways from lower domains to higher elevations as well.

Kala Weva, which is one of the magnificent reservoirs of the ancient world, could be sighted as a typical example where water had been diverted to Tisa Wewa (an artificial reservoir, built by King Devanampiyatissa during the 3rd Century BC) on a higher elevation. To accomplish this task construction of Yoda Ela, which is 56 miles long with a gradient of one inch to a mile, remain as a living example.

tilakfernando@gmail.com