The Travels of a Journalistâ€â€ÂÂ70-On Rio Grande route to San Antonio,we learn about Bean & border blasters;in city, we visit Alamo & do River Walk

Posted on June 10th, 2011

By Shelton A. Gunaratne ƒÆ’-¡ƒ”š‚© 2011 Professor of mass communications emeritus at Minnesota State University Moorhead

After the arduous exploration of the Big Bend NP and a cozy overnight in Sanderson (pop. 861) in Terrell County, weƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚daughter Carmel, son Junius, wife Yoke-Sim and IƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚left our motel at 7.30 a.m. Friday (29 Nov. 1991) to continue our return journey east to San Antonio (pop. 1.3 million), TexasƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢ second largest city. Whereas we traveled on Interstate 10 on our forward journey to Big Bend, we were now traveling on U.S. 90 on our return journey so that we could drive parallel to the eastern section of Rio Grande as it meandered its way through Brownsville to its confluence with Gulf of Mexico.

Our first stop was Langtry (pop. 145), 61 miles from Sanderson, in Val Verde County. Originally established in 1892 as Eagle Nest, a grading camp for railroad workers, it was later named after George Langtry, a railroad engineer and foreman who supervised immigrant Chinese workers. But today this small community has gained a touch of notoriety as the place where “Judge” Phantly Roy Bean Jr. (1825-1903), the “Law West of the Pecos,” had his saloon and practiced a kind of law. Curiosity forced us to stop at the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center, where we also thoroughly enjoyed the botanical garden with native desert plants. Legend has it that Bean, who came from Kentucky, held court in his saloon along the Rio Grande in a desolate stretch of the Chihuahuan Desert of Southwest Texas.

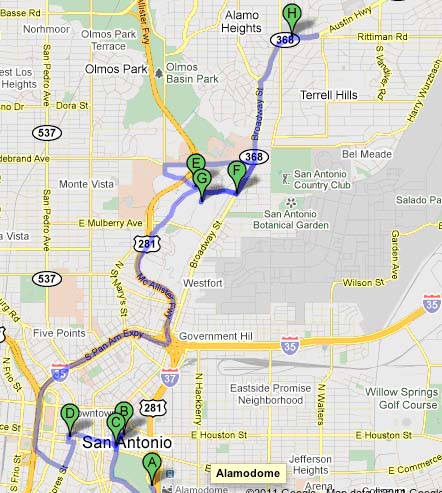

Figure 1: The Rio Grande route from Sanderson to San Antonio (286 miles):A=Sanderson; B=Langtry; C=Amistad Dam/Amistad Reservoir; D=Ciudad AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a in Coahuila, Mexico; E=Del Rio; Brackettville; F=Uvalde; G=Castroville; H=San Antonio.

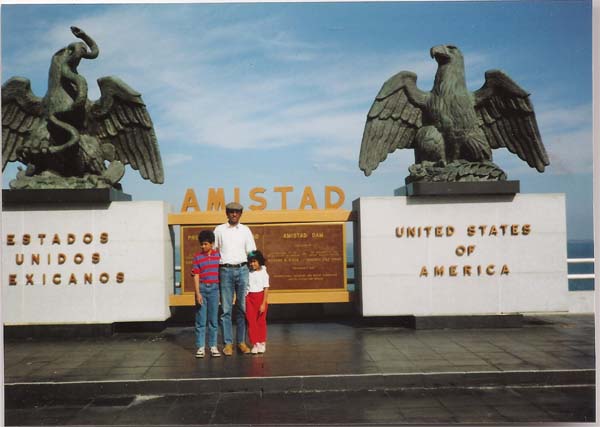

From Langtry, U.S. 90 runs southeast parallel to Rio Grande for 60 miles all the way to Del Rio (pop. 44,286), the administrative seat of Val Verde County. On this stretch of the road, we stopped at Pecos River Picnic Area for refreshments. Then, we crossed the 26,300-hectare Amistad Reservoir and the surrounding recreation area on Rio Grande at its confluence with Devils River and stopped to view the impressive Amistad Dam (completed in 1969) on the U.S.-Mexico border. Here, we were thrilled to cross over to the Mexican state of Coahuila and drive the 14 miles to Ciudad AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a (pop. 134,233), where we ate lunch at San Andres Fried Chicken Cafeteria on Ave. Lopez Mateos for just $5.50!

PICTURE 1: The author with Junius (left) and Carmel on the U.S. border with Mexico at Amistad Dam before they crossed over to Coahuila State for a 14-mile drive to Ciudad AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a (29 Nov. 1991)

I learnt that this was the border city wherefrom radio pioneer John R. Brinkley, a U.S. citizen, began the era of Mexican border ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-blaster radioƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚radio stations broadcasting from various Mexican cities near the border to attract U.S. advertising. In the 1930s, these border stations had to operate under the laws of Mexico. In 1933, the Mexican government shut down a Brinkley-controlled station named XER-AM (in what was then called Villa AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a). However, in 1935, the government gave the OK to a border blaster with the call letters XERA, also controlled by Brinkley but ostensibly owned by RamƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚³n D. BƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚³squez Vitela. Wikipedia elaborates:

Brinkley used the old buildings of XER but installed a new 500 kilowatt transmitter. The new directional antenna of XERA allowed Brinkley to claim that his station had an effective radiated propagation of one megawatt. One of his Texas engineers called XERA “the world’s most powerful broadcasting station.”

But XERA also came to a halt in 1939 when Mexico revoked the stationƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s license. XERF commenced operations in 1947 as a new station (now branded as La Poderosa or ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-the PowerfulƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚) using the old facilities of BrinkleyƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s XERA but with no other connection to Brinkley.

After mulling over the birthplace of border blasters, we paid a toll of $1.95 to cross the Del RƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚o-Ciudad AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a International Bridge to return to the United States. Del Rio lay six miles to the northeast of AcuƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚±a. At the bridge, Rio Grande and we also had to end our parallel company. We continued to drive east on U.S. 90 to San Antonio while the river turned southeast eager to dislodge everything it carried in its belly into the mighty gulf. The Whitehead Memorial Museum downtown preserves the history of Del Rio. Just to the east of Del Rio is Laughlin Air Force Base, the busiest pilot training base in the U.S. Air Force.

Next, we stopped at Brackettville (pop. 1,876), the seat of Kinney County. Founded in 1852 as Las Moras (the name of a nearby spring and the creek it feeds), the town was later renamed Brackett after Oscar B. Brackett, the owner of the first dry goods store in the area. Tied strongly to nearby Fort ClarkƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s fortunes, BrackettvilleƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚suffix ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-villeƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ added in 1873ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚had a larger proportion of Black Seminoles (people of mixed African American and Seminole ancestry) than the rest of West Texas. Their language, Afro-Seminole Creole, is still spoken by some in Brackettville. North of town is a tourist attraction called Alamo Village, built in the 1950s as the set of John Wayne’s movie The Alamo (Wikipedia).

We passed through Uvalde (pop. 14,929), the seat of Uvalde County. When Reading Wood Black founded the town in 1853, it was named Encina. Three years later, a reorganization of the county made this town the county seat and renamed it for Juan de Ugalde (1729-1816), the Spanish governor of Coahuila from 1777-1783. Wikipedia says that Uvalde is usually considered the southern limit of the Texas Hill Country or the most northerly part of South Texas. The town has the only known bottler of cactus juice. Another attraction is John Nance Garner Museum memorializing the vice president of the United States from1933 to 1941.

When we reached the western outskirts of San Antonio, we stopped at Castroville (pop. 2,664) in Medina County to visit the Landmark Inn State Historic Site featuring a series of cut limestone structures laid up with adobe-type mortar and covered with whitewashed lime plaster. The solid stonewalls of the buildings (of an inn established in 1824) vary between 18 and 24 inches thick. What attracted our attention most was the two-story stone bathhouse that has an exterior stair and balcony. According to tradition, the upper room, which served as a tank, was lined with lead. During the Civil War, the Confederates melted this lead to furnish bullets for use.

Exploring San Antonio

Following our foray into Big Bend NP, we returned to downtown San Antonio (see Travels-67) about 4.30 p.m. Friday (29 Nov.) just in time to visit the Institute of Texan Cultures (801 E. Durango Blvd.) in HemisFair Plaza, a short walk from the Alamo and the River Walk, two of the outstanding tourist attractions in San Antonio. Inaugurated in 1965, the institute is part of the University of Texas at San Antonio. It serves as the state’s primary center for multicultural education, with exhibits, programs and events like the Texas Folklife Festival, an annual hcelebration of the more than 26 ethnicities that make up the population of Texas.

Next, we drove through a traffic snarl to visit the Alamo (300 Alamo Plaza), an edifice built in 1718 to house Mission San Antonio de Valero, a Roman Catholic mission and fortress compound. It was the site of the Battle of the Alamo in 1836, in which the Texan army defeated the Mexican army. The chapel of the Alamo Mission is known as the ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Shrine of Texas Liberty.ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚ We toured the chapel, as well as the Long Barracks, which contains a small museum with paintings, weapons and other artifacts from the era of the Texas Revolution. We saw additional artifacts displayed in another complex building, alongside a large diorama that recreates the compound as it existed in 1836. A large mural, known as the Wall of History, portrays the history of the Alamo complex from its mission days to modern times. About 5 million people visit the Alamo every year. (Admission is free)

Figure 2: Attractions we visited in or near Downtown San Antonio:

A=Institute of Texan Cultures; B=the Alamo / ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ…-Shrine of Texas LibertyƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚; C=River Walk along San Antonio River; D= Spanish GovernorƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s Palace; E=San Antonio Zoo and Aquarium; F= Witte Museum; G= Brackenridge Park; H= McNay Art Museum.

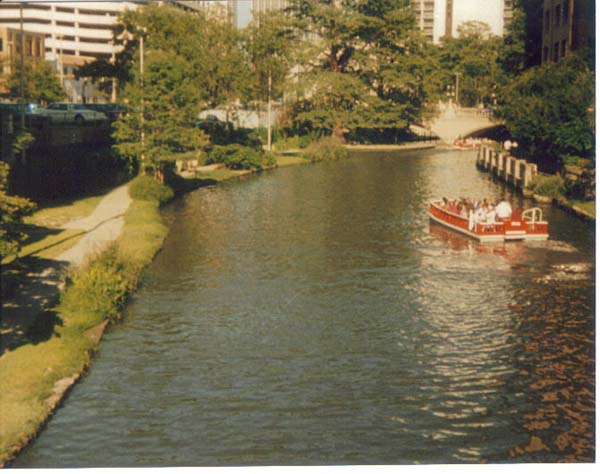

From the Alamo, we turned into the River Walk (also known as Paseo del RƒÆ’†’ƒ”š‚o), a network of walkways along the banks of the San Antonio River, one story beneath downtown. Bars, shops and restaurants lined the River Walk as an important part of the city’s urban scene.

The River Walk winds and loops under bridges as two parallel sidewalks lined with restaurants and shops, connecting the major tourist draws from the Alamo to Rivercenter mall, to the Arneson River Theatre close to La Villita, to HemisFair Park, to the Tower Life Building, to the San Antonio Museum of Art, and the Pearl Brewery. During the annual springtime Fiesta San Antonio, the River Parade features flowery floats that literally float. (Wikipedia)

PICTURE 2: A view of the San Antonio River Walk (1997)

Photo by Billy Halthorn. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

We learned that the idea to create the River Walk came up as a solution to the 1921 devastating floods that engulfed San Antonio killing 50 people. Work on the project began in 1926 under the able guidance of architect Robert Hugman.

We found walking along the River Walk difficult because of the vast crowds that had gathered to see the River Walk Lighting Ceremony and Holiday River Parade. However, we enjoyed joining the crowds and viewing the parade. We also visited La Villita while waiting for the parade. After eating dinner at the downtown MacDonaldƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s, we drove all the way to the Best Western TownhouseƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚the same motel we stayed on Saturday (23 Nov.) on our first arrival in the cityƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢¢”š¬‚to spend the night.

(I did a much more thorough exploration of the River Walk when I returned to San Antonio 14 years later to attend the AEJMC Convention in 2005 (11-13 Aug.)

Northwest informed us Saturday (30 Nov.) that we had to spend another day in San Antonio because weather conditions prevented the airline from landing in Minneapolis. National Car Rental rented us another Ford Taurus automatic for a day when we returned the car we had rented for a week. Thus, we spent another day exploring San Antonio. Among the spots we decided to visit were:

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚¢ The Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum (600 N. New Braunfels Ave.), where we spent about one hour in the delightful surroundings of a 9.3-hectare garden. The museum, opened in 1950, was named after American painter McNay, and has been expanded to include galleries of medieval and Renaissance artwork and a larger collection of 20th-century European and American modernist work. (Admission: free)

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚¢ The 14-hectare San Antonio Zoo and Aquarium in Brackenridge Park (3903 St. MaryƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s St.), where we spent a couple of hours looking at a collection of some 3,500 animals representing 750 species. The zoo’s annual attendance exceeds 1 million. (Current general admission: $10.75) We ate lunch at the adjoining sunken oriental garden.

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚¢ The Witte Museum (3801 Broadway), which focuses on the natural sciences with emphasis on South Texas and the history of Texas and the Southwest. It is dedicated to the history, science and culture of the region. The permanent collection represents ethnography (study of social and cultural change), decorative arts and textiles, and science. (Current general admission: $8)

ƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ”š‚¢ The Spanish GovernorƒÆ’‚¢ƒ¢-¡‚¬ƒ¢-¾‚¢s Palace (at Camaron and West Commerce) on Military Plaza. The keystone above the front entrance contains the coat-of-arms of Spanish King Ferdinand VI along with the date 1749. Wikipedia says the building was actually the residence and working offices of the local presidio captain, and not the palace for the region’s Spanish governor. (Current general admission: $2)

Because Carmel and Junius started to show signs of boredom, we returned to our motel late afternoon to rest and get ready for our return journey to Minnesota. Sunday (1 Dec.), we returned our rented car to National Car Rental agent at San Antonio Airport, where we boarded the 6.10 a.m. Northwest flight to Memphis.

[The Sunday edition of The Forum (9 Feb. 1992), the daily newspaper of Fargo, N.D., published a condensed and different version of our Texas adventure.]

June 12th, 2011 at 11:13 pm

A lot of Lankaweb server space wasted on 70 volumes thus far!

June 15th, 2011 at 8:04 am

You, again!

Next time you complain about wasted space in social media, do so under your real name.Also, specify what you mean by “wasted space.”

I have written more than 100 travel and autobiographical stories to excite people to get into recreational activities. I presume that armchair yawners like you have no interest in geography, culture, literature or anything outside politics anti-Western rhetoric.