Should Sri Lanka engage LNG floating regassification vessel for electric power?

Posted on November 7th, 2021

by Nalin Gunasekera Courtesy The Island

In many countries, an LNG project is the largest investment ever undertaken, and a country’s future creditworthiness may hang in the balance. Unfulfilled commitments for any reason can lead to millions of dollars of losses.

LNG – A Non-Technical Guide by Michael Tusiani, 2011

The writer Nalin Gunasekera (nalin.gunasekera@hotmail.com) has spent 40 years in the oil and gas industry and many years in leasing and operating floating LNG regassification vessels in more than 10 countries, representing Royal Dutch/Shell, Mitsui and Mitsubishi, the largest LNG vessel owner/operators and LNG traders in the world. Shell is the licensee for the largest gas reserves in the world and the custodian of gas and floating systems technology. Nalin received the Anniversary Technical Excellence Award from Shell for a floating system regarded as a ‘market trend setter’. He trained as an engineer in the University of Ceylon and at University College London as a government post-graduate scholar. He lives in Australia, the largest global LNG producer in 2021 and host to the highest density of floating production vessels in the world, and the technically most advanced ever built, Prelude, by Shell, costing US$ 12 billion. Nalin has participated in the roles of client, consultant and contractor, representing the largest institutions in the industry.

Part 1

(Part 2 to follow will cover FSRU technology, commercial transactions, LNG procurement, LNG suppliers, HSSE (health, safety, security, and environment), insurance, jurisdictions, future challenges to LNG, and regional energy policy changes.)

Where are these FSRUs today and where are they planned in the region?

Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) seeks to join the region consisting of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar, Philippines, Vietnam, and Cambodia, in turning to regassified LNG as an energy source to supplement others by installing an FSRU. South and South-East Asia are becoming the epicentre in LNG regassification, with these countries turning to a gas-based-economy to benefit from increasing LNG supply globally with lower harmful emissions compared with coal and oil.These countries have recognised that LNG although not ‘green’ will nevertheless be needed to assist the economy to transition to net zero carbon emissions (NZE), even if the immediate outcome is not NZE. Some countries in the region have more than one FSRU in operation or planned since India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh already have their LNG regassification initiatives proven to be wise decisions.According to Natural Gas World, in 2020, eight new FSRU terminals were installed/commissioned in Bahrain, Croatia, Brazil (two), India, Indonesia, Myanmar and Puerto Rico (out of a total of about 50). Vietnam with its long shoreline is planning for 130 GW of power generation with LNG, supported by four FSRUs, with Exxon-Mobil investing in their transition to gas. Cambodia is planning to have 3,600 MW of LNG powered power generation by 2030 with Japanese and Chinese assistance and have FSRUs planned.Countries such as India, Bangladesh, Brazil, Indonesia with two FSRUs, have their own natural gas domestic reserves currently in production; they are however supplementing with regassified LNG from an FSRU. Their LNG may be sourced overseas rather than locally.

The current self-funded proposal by NFE for Sri Lanka (SL) is with payment guarantees by the US Government. This is most welcome at a time when SL is desperate to attract foreign direct investment to provide confidence and credibility to the global investor community.

Would Mannar Basin reserves development be threatened by the FSRU?

The Mannar reserves if developed will supplement natural gas from the FSRU, it will not be a threat.

Australia and Qatar are the largest LNG suppliers worldwide supplying about 75mtpa (million tons per annum) each out of a global total of about 350 mtpa. Despite this LNG trade dominance, Australia is planning to have at least three FSRUs: one by Vopak, in Port Philip Bay Victoria, the second by Viva Energy, in Geelong, Victoria for delivery in 2024, and the third in Port Kembla NSW. This is because LNG shipped to FSRUs is more cost-effective than installing long pipelines from remotely located natural gas production plants. Australia may not be regassing their own LNG (locked up in long term contracts) but will be regassing LNG from the open market on possibly long-term-take-or-pay contracts. They have sought two guaranteed gas buyers on take-or-pay terms to finance the project who possess AAA high investment-grade-credit-ratings to minimise risk to the investor.

Indonesia, a major exporter of LNG of about 25 mtpa with their own natural gas production network is turning to FSRUs.

What are the prospects for the Mannar development?

Deep water reservoirs for development are for those with very deep pockets. Their risks are severe and the outcomes uncertain.

An overhead slide from a deep-water presentation

The Mannar field is a deep-water development with two wells drilled 30 to 60 km from shore in 1,350m to 1,500m water-depth. If this field had been appraised to be feasible, its development would have competed with the FSRU.In countries such as in India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, Myanmar, Brazil and in many others, domestic natural gas production supplements the FSRU. The two complement each other. However, the prospects of the Mannar basin must be reviewed in the current context.

The development of petroleum resources requires the government to enter into a partnership with oil companies. It is the oil companies that have the financial strength, expertise, and capacity/capability to explore the resources. They possess the requisite technology and skills to develop the resources and are willing to assume the financial risk.

The parties have different goals and agenda. The government’s primary focus is the benefit of the country, while the oil companies’ goal is maximising shareholder returns. There is tension in reconciling the value‐laden goals of governments with profit-oriented goals of the companies. Yet there is also some synergy for the two parties, government and oil company, in trying to maximise returns to their respective stakeholders.

The oil industry has already lost its appeal to investors. Any financing from capital markets will face challenges given the need to be transparent in disregarding policies of monetary authorities and investor banks concerning divestment and avoidance of fossil fuel investments. The banks would face a backlash from the public who would be concerned about their shareholder returns, in the context of today’s focus on COP 26 goals. Fossil fuel projects will therefore largely require self-funding, for which the oil companies have no appetite today. Having made losses in the past years, oil companies are selling off their assets to pay dividends, and do not see a future. They are cutting staff regularly.

Deep water developments are costly requiring much larger reservoir sizes to justify investment. Since the Indian exploration company Cairn left SL in Jan 2007 due to the discovery of low reserves, there has not been any noteworthy investment in appraising the Mannar field. Further, the field is not close to landfall and may require subsea infrastructure and high pressure boosting of the reservoir. The writer is able, from his own experience, to confirm that these sub-sea facilities are prone to failure. These marginal fields for development require a recognised, credible, independent-third-party-verification for investment. This has not been done.The expectation today is that several viable fields ready for development will not be monetised, being unable to access finance. The projection is that 30% to 40% of viable fields may never be monetised. This is given the ‘perfect storm’ created by the recent crash in oil and gas prices (now rising suddenly, which may be temporary with future trajectory unknown) as well as Covid-19 and UNFCCC COP 26 potential mandates against fossil fuel. However, this may change if the 2050 NZE targets are unviable.

Deep water technology is largely with the majors such as Shell, Exxon-Mobil, Chevron, TOTAL, etc. They have made significant losses in recent years and are unable to self-fund having no access to finance.

Complex subsea architecture in deep-water Mannar is remotely located and in the event of failure require subsea intervention. Physical diver intervention is not possible due to the depth of water in excess of 1.3 km. The intervention facilities, DP DSV ROV (dynamically positioned diving support vessels with remote operated vessels) are extremely expensive to mobilise/demobilise, costing USD 10 mil or more when remote. (The writer was involved in remote deep-water interventions where fields have been abandoned due to intervention costs being unjustifiable and the outcomes uncertain).

SL’s investment grade is so low that for any field development the financing costs above LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate) will be extraordinarily high. This is reflected in the country’s status of ‘default category with no prospect of recovery’ by rating agencies such as S&P.

These marginal investments are considered high risk being still at the pre-development exploratory stage and since Jan 2007 have not been able to attract an oil company for exploratory wells.

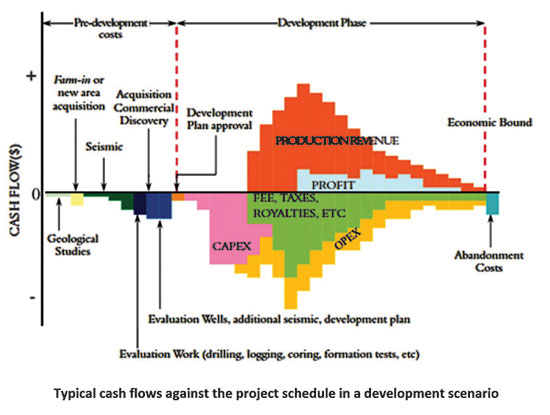

Given their marginal nature, oil companies expect a disproportionately high return with minimal or no taxation/royalties for their investment as they have significant outgoings. It is not unusual for governments who are new to the industry to end up with minimal or no revenue; ultimately left with facilities with a significant negative value to be removed at the taxpayer expense.A typical project to be executed may take several years as seen above with many uncertain outgoings. Australia’s major gas field Browse which commenced exploration in 1967, and has already been appraised to be viable for investment with 12 TCF (Trillion cubic feet) of recoverable gas, is continuously postponed given the global uncertainties.However, when the future of the industry was certain, there have been oil fields that were delivered in 14 months after appraisal, unlike today when the future is uncertain.

The Mannar field, at best, may have to wait to be developed until the investment climate improves and the uncertainties are minimised.

Is there a risk to SL if the FSRU is not installed by NFE?

The past three/four GoSL FSRU tender invitation attempts, were only meaningless academic exercises with no guarantee of payment by an investment grade credible entity. The GoSL is akin to someone seeking to purchase a new Rolls Royce with insufficient money to buy an old Morris Minor, and then engaging highly paid consultants who see ‘cash in chaos’, and take the GoSL for a ride. The last invitation to tender proposed under Swiss Challenge process against SKE&S’s unsolicited proposal did not attract a single prospective bid after more than four or five extensions to the closing date of tender over about eight months.

The current CEB tender is no different with no guaranteed payment security package by a credible investment grade party offered to the bidders. This will eventually be required. A toxic combination of misinformation in the public domain and unregulated malfunctioning of the electricity sector by the Ministry of Power and CEB has crippled SL’s economy perhaps beyond repair. Understandably they will attempt to wrest control over this project from any other competing ministry.India faced many challenges similar to SL in these projects in countering misinformation in the public domain by self-appointed experts, who had no exposure to industry norms, complex technology, or any understanding or experience in the highly specialised nature of offshore oil and gas business and their complex commercial transactions. SL is not any different with misinformation from (a) ideologues who see energy transition to NZE without intermediate steps such as LNG or other realistic options, (b) those with vested interests in importing coal and diesel, (c) ignorance of the complexity of industry norms, and (d) complete ignorance and disregard of the industry state of play. These cannot be understood overnight by those with vested interests, and others in isolation who are making outlandish demands. They create confusion amongst themselves, with the public at large, policy formulators and decision makers.If this FSRU is not installed, there is a likelihood that the power generation with diesel will continue and expand with increasing unbearable losses and environmental damage, which has been the past record in power generation. Under the new international consensus that may develop following UNFCCC COP26, countries continuing with heavy reliance on coal and oil may face punitive measures such as carbon tariffs on exports and other trade and commerce.

What is an FSRU? How does an FSRU work?

A Floating Storage and Re-gasification Unit (FSRU) is a floating vessel that is permanently moored at a site where it can receive LNG from tankers/carriers, store and regasify the LNG and send it as natural gas to shore via a subsea pipeline at a rate required by the natural gas users. The natural gas upon receipt at landfall from the FSRU would be transferred via pipelines on land to the end user power generators such as at Kerawalapitiya.

NFE will be supplying an FSRU and the associated pipelines. The project components are leased being supplied under EPCIC (Engineering, Procurement, Construction, Installation and Commissioning) and O&M (Operation and Maintenance) terms of responsibility for a specified period called the ‘fixed term’ with a period of optional extensions at predetermined commercial terms.

The figure above shows Moheshkhali FSRU Bangladesh with its submerged turret loading mooring and dynamic riser which is exposed to monsoons, operating since 2018. The vessel has a disconnectable mooring which disconnects from the vessel by lowering the swivel during high storm surges (such as monsoons as experienced in SL) and reconnects when the weather is benign. The vessel ‘weathervanes’ (rotates) about the single-point-mooring with the meteorological oceanographic variations in wind, wave and current. The vessel motions are determined analytically and verified by model tests to meet Classification Society requirements. There are other forms of shallow water moorings.

The mooring and riser technology is proprietary and technically complex in which the writer has specialized along with their commercial transactions in vessel leasing and operations.

A dis-connectable mooring system is where the floating installation has a propulsion system and a means of disengaging the installation from its mooring and riser systems to allow the installation to ride out severe weather or seek refuge under its own power for a specified design environmental condition.

A disconnectable moored vessel requires a full marine crew, must be flagged as required by IMO (International Maritime Organisation) with the vessel likely being in transit during its tenure. The writer has supplied many of these complex mooring systems which remain proprietary technology.This is completely new technology to SL, lacking any exposure to offshore oil and gas industry standards, codes, practices, industry norms, risks, analytical methods, Classification Society Rules under which they are designed and constructed, their insurance requirements, health safety and security and environmental practices, and complex multiple jurisdictions. Their commercial transactions are notoriously complex.NFE would remain as the single point responsible for all components up to the end user of the gas. The removal of the installation or transfer to the GoSL at the end of the lease is an option. In the case of SL, the vessel will be handed over to GoSL for continued operation after 10 years. In some countries the vessel when handed over has been a liability being a ‘rust bucket’ having a considerable negative value requiring the taxpayer to fund its removal, costing more than USD 50 mil. The ability of GoSL to undertake the operation and maintenance at hand over may raise questions (as in securing insurance such as P&I insurance, to be explained in Part 2), when the operator’s competency will be questioned by the insurer. This is a form of due diligence in determining GoSL’s capability to operate the facility by an independent third party. These are lessons to be learnt from cases in South East Asia, when vessels were handed over with unintended consequences.

November 9th, 2021 at 5:58 pm

Sri Lanka is a country which is constantly on an enterprise to ‘rediscover the wheel’ in every field of national endeavour. They ‘ go where Angels fear to tread’ with dogged confidence. This is the reason why it is not possible for Sri Lanka to make headway in any field – simply because of inexperienced ‘professionals’, blundering and corrupt administrators (SLAS) and gullible politicians!

They talk of gas from Mannar Fields as if it is easy as going to the gas station in town. Estimates of gas in the ground is being shown as if it is already ‘money the bank’!

The writer above explains the process well. දැන ගියොත් කතරගම, නොදැන ගියොත් අතරමග!

November 9th, 2021 at 9:13 pm

Nalin G,

You have the brains, but no means!. This is common to all SL’s. Vega EVX, Tony Weerasinghe’s StackMarket engine and many more suffered same. Politico’s of SL and their mediocre admins (like SLAAS) will block you unless they have a share.