Why the Portuguese lost the battle of Randeniwela

Posted on January 27th, 2026

Courtesy The Daily Mirror

This was the first time that a Portuguese army was completely wiped out in battle. This gave King Senarat the possibility of ending Portuguese domination by taking the fortress of Colombo. As we have seen, he failed to do so because the Sinhalese forces lacked the necessary artillery power and the naval power

We have already seen how Constantino de Sa, perhaps the ablest Portuguese captain general to arrive here, worked hard to stabilise the Portuguese position in the coastal and low-country areas under their control before finally setting off to invade Kandy. Conquest of the troublesome kingdom in the hills would have pleased the viceroy of Goa as well as the king of Portugal, and consolidated his position as Jaffna was already under his control.

We have already seen how Constantino de Sa, perhaps the ablest Portuguese captain general to arrive here, worked hard to stabilise the Portuguese position in the coastal and low-country areas under their control before finally setting off to invade Kandy. Conquest of the troublesome kingdom in the hills would have pleased the viceroy of Goa as well as the king of Portugal, and consolidated his position as Jaffna was already under his control.

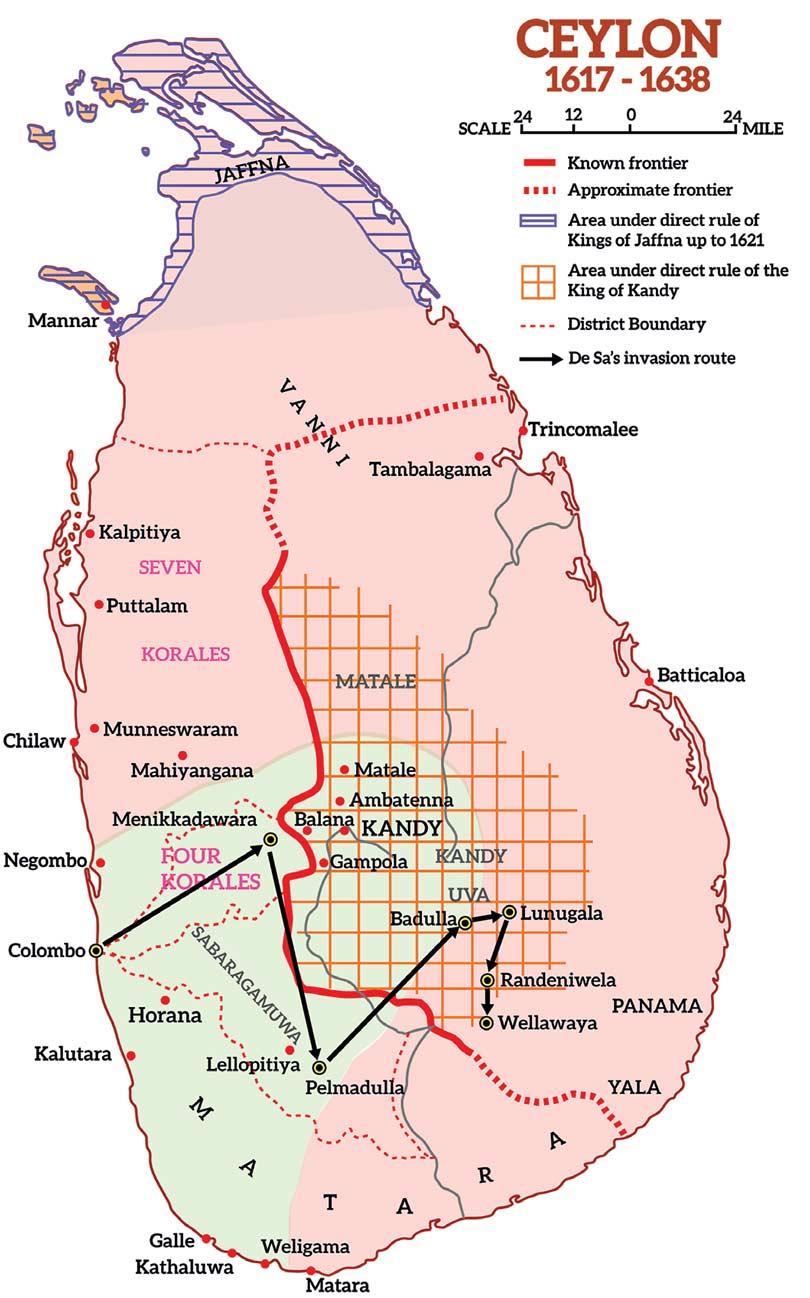

De Sa’s unconventional invasion route of 1630 De Sa’s unconventional invasion route of 1630Source: Derived from C.R. de Silva’s book ‘The Portuguese in Ceylon 1617-1638’ |

After putting down a plot to hand over the fort of Colombo to King Senarat’s forces by stealth, De Sa began his ambitious invasion of Kandy on August 3, 1630 with high hopes. He had assembled a large army for the 17th century – 628 Portuguese soldiers (including 120 armed landowners enlisted for the invasion), and 4,500 lascarins.

Portugal’s principal problem in running a far-flung empire was manpower. In 1500, the country had only 1.1 million people. This led to a policy of hiring local mercenaries to fight their wars in colonies. In Sri Lanka, this was the Achilles’ heel in Portuguese military strategy. The loyalty of the lascarins (local mercenaries) was crucial to both their defences and offensives. If the lascarins deserted, De Sa had less than 700 soldiers to rely on. Thus, he had done his best to secure the lascarin commanders’ loyalty.

Why he didn’t take the traditional invasion route via Balane Pass to Kandy remains a mystery. He had already led an expedition to Balane, taking the Sinhalese stronghold, and then retreating to Colombo. He did this in late June 1629, during the southwest monsoon, losing many men to sickness, soldiers having to fight leeches and reptiles as well the Kandyans. His army reached Kandy and burnt it, but his men were exhausted and the army retreated to Manikkadawara with both sides claiming victory. De Sa is known to have fallen ill before this, and one can only conclude his judgement was impaired as a result.

It is possible that (this is my own theory), being a nobleman, he may have read about Rome’s wars with Carthage, and about Carthagian general Hannibal crossing the Alps to attack Rome from the rear. As all traditional invasions of Kandy had failed, he may have believed that a very daring and unconventional approach might succeed.

He chose to take a very difficult southern route to Uva across the Idalgashinna Pass. This expedition is the best documented of all Portuguese invasions of Kandy, and we have a very clear picture of what happened. The army started from the fort at Menikkadawara on August 3, 1630, and marched leisurely to Sabaragamuwa. From there, they began marching into Kandyan territory on August 9.

The army had to take a circuitous route through the Pelmadulla Gap to avoid the tough Rakwana Hills. After marching sixty miles through forests with no roads and having to forge streams, it arrived at Haldummulla (1000 metres above sea level); the worst parts lay ahead, a climb of 2,500 feet within two miles through jungle up to the frontier post at Idalgashinna. This was ideal country for guerrilla warfare.

But the Kandyans withdrew, drawing the Portuguese army further into the trap. Anyone who has trekked in these areas would know how tough the climb is, and this was an army carrying weapons, gunpower and provisions. After Idalgashinna, though, they were in open country with gently undulating hills.

This is the Uva Basin, with Badulla at its centre. De Sa reached Badulla on August 15, and set fire to the settlement. By the time he realised that he was being encircled by King Senarat’s Kandyan army of 12,000 men, he was already trapped. The Kandyans had only 1000 muskets, but even so, the Portuguese had reasons to worry. De Sa realised that the invasion would have to be cancelled and retreat was the best course.

He had another worry; news of a planned defection by his lascarin commanders. Trying to pacify them, De Sa promised to reward them when they reached Colombo safely. He kept the lascarin soldiers at the front and the rear as the retreat began on August 21, thus keeping his Portuguese force intact.

But his retreat was blocked by forces led by princes Kumarasinha and Vijayapala; and Dom Jeronimo Rajapakse, one of the lascarin commanders, defected, leaving De Sa’s flanks unprotected. This was the signal for the others to follow. Dom Cosmo, killing the Portuguese nearest to him, deserted with his forces, followed by the other lascarin commanders Dom Aleixo, Dom Theodosio and Dom Balthazar.

De Sa’s position was now desperate. Some of the lascarins were still with him, but he could not trust them not to desert. As the Idalgashinna route was now blocked, he was forced to retreat southeastwards, even further away from safety.

By superhuman efforts, the Portuguese managed to reach the Lunugala Hills, suffering heavy losses. The next day, the Kandyans cut off the rear guard led by disava Luis Texeira Macedo and took 22 prisoners. Finally, on Tuesday August 22, the remnants of De Sa’s army were completely surrounded in an open field at Randeniwela. By 2 p.m., after two hundred Portuguese had fallen, the captain general himself was killed. The remainder surrendered an hour later.

This was the first time that a Portuguese army was completely wiped out in battle. This gave King Senarat the possibility of ending Portuguese domination by taking the fortress of Colombo. As we have seen, he failed to do so because the Sinhalese forces lacked the artillery power to batter down the fortress walls, and the naval power necessary for a maritime blockade.

Thus, this tug of war continued, and led to the next Portuguese disaster in the battle of Gannoruwa which, as historian C. R. de Silva points out in his ‘ThePortuguese in Ceylon 1617-1638,’ signalled the end of Portuguese dominance in the island, though not the end of Portuguese rule.