SOME OBSERVATIONS ON EARLY BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA Part 1

Posted on March 22nd, 2020

KAMALIKA PIERIS

Gautama Buddha lived and preached in the Uttar Pradesh and Bihar regions of north India in the 6th century BC. The 6th century BC is of great significance in North India. The 6th century is considered the beginning of the Early Historic Period of India. This period also corresponds to the classical period of ancient Greece.

Significant social changes took place in north India during the Early Historic Period. This period saw the establishment of urban civilization with a literate culture. There was writing. During this time, a religious and economic reform movement started in the Ganges region. It was an ‘age of amazing religious creativity,’ which saw the rise of as many as 62 religious sects, said, scholars.

Prominent among them was the reclusive, itinerant Sramanas, highly critical of Brahmanism. Different Sramana groups held different views, with no consensus. The region was a beehive of religious activity. The religious sects were actively competing with each other.

From this religious ferment came two new religions, Jainism and Buddhism. Siddhartha Gautama’s entry into the fray was well calculated, said Ven. Bellanwila Wimalaratana. It is now accepted, that Siddhartha left the palace openly, with the knowledge of his parents. He did not creep away secretly in the night, as romantically depicted. It is stated in Ariyapariyesana sutta, that he left home with his parents shedding tears.

The Ganges region had a full-fledged iron age by the sixth century BC. This led to a tremendous expansion in agriculture, which led to the growth of trade and commerce, which, in turn, led to a money economy. The earliest coins discovered in India are dated to the time of Gautama Buddha and beyond. These coins were issued by the merchants and bore punch-marks. The use of coins in this period seems to have become fairly common and even the price of a dead mouse is stated in terms of money.

Trade led to the emergence of towns and cities. Remains of these urban centers have been found in archaeological excavations. The Vedic literature of the period says nothing about cities. The Buddhist texts, on the other hand, are full of references to and descriptions of cities and towns. These towns and cities are labeled ‘nagaras’ and ‘puras’, distinct from villages, ‘gramas.’

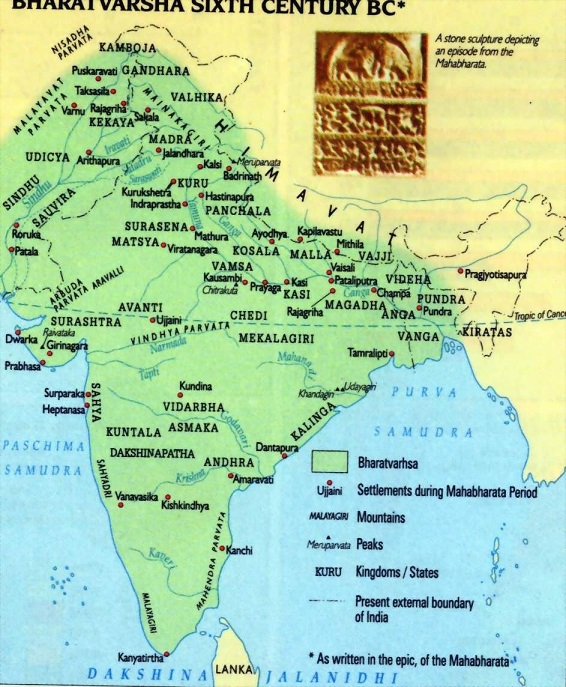

As many as sixty cities figure in the Pali canonical texts. Six of these cities stood out, Champa (near Bhagalpur, Bihar), Rajagriha (Rajgir, Bihar), Varanasi (Benares,), Kausambi (Kosam near Allahabad,), Sravasti (Sahet-Mahet, UttarPradesh), and Kusinagara (Kasia in eastern Uttar Pradesh). All these cities were located in the middle Ganges valley.

Some urban centers, such as Ujjayini and Taxila, functioned as political and market centers. Others, notably Varanasi and Sravasti were cultural centers as well as political and commercial centers. Buddhism and Jainism were more popular in these urban centres than in rural areas.

During this period, for the first time in Indian history, there arose political states. They were known as mahajanapada and janapada. The word janapada means a populated territory. Both Buddhist and Jain texts mention sixteen such states.

Many of them were much bigger than Greece and some of them were in existence up to the Maurya Empire. But apart from the Sakyas and Lichchavis, very little is known about the political history of these states

Not all states were kingdoms. Some were governed by councils of nobles . Modern scholars have labeled these as republics”. These were the only republics of the time, outside the Mediterranean.

The merchants, officials and those based in towns found the existing Vedic religion unsatisfactory. They did not like the fact that the Brahmin caste dominated religion. They also did not like the rigid caste system embedded in the Vedic religion, and the compulsory rituals and sacrifices.

They wanted a religion that would abolish the supremacy of the Brahmin priestly class and do away with ‘Hindu’ caste. They began looking for a new religion, which would suit their needs. There were plenty of sects to choose from. They settled on Buddhism, which spoke against caste and Vedic rituals. Buddha dispatched 60 disciples to propagate Buddhism. They were asked to go in different directions.

Buddhism took off to a fine start, targeting kings, nobles and top traders. The first converts were the three Jatila brothers, Uruvelakassapa, Gayakassapa, and Nadikassapa who ruled Uruvela (Bodhgaya). Gautama Buddha thereafter concentrated on converting royalty to his beliefs (Bimbisara, Pasenadi) and after that, the rich traders (Anatapindika). The advantages were obvious. Where kings led, subjects followed. The traders provided money for further expansion of the religion. They also helped to spread it, traveling up and down the trade routes.

Kings, nobles and rich merchants accepted the Buddha when he was alive, and gave him food and other necessities. The Buddha and his disciples often accepted invitations to the houses of the rich men for the midday meal. However, they also accepted food and other requisites given by those who were not rich.

Gautama Buddha discoursed on many lay matters, including the creation of cities. He commented on various aspects of public life and concerns of government. He spoke of the righteous king. Pali commentaries discussed both the republican government and monarchy.

The traders and merchants wanted a religion that would specifically support trade. Buddhism obliged. Trade was not held in high esteem in the Vedic tradition. In sharp contrast to the Vedic attitude to trade and merchants, Gautama Buddha said trade (vanijja) was an excellent profession.

The Buddhist texts refer to a wide range of merchants, from rich setti to caravan traders travelling to distant places. The traders and merchants also wanted religious approval for foreign trade and sea voyages. The Vedic religion did not approve such voyages for Hindus. Buddhism approved sea-voyages.

Buddhism and trade thus went hand in hand from the very beginning. Trade was the main conduit for the transmission of Buddhism from India . Not only people and goods but ideas and religion also went along the Indian trade routes, said, scholars. The Archaeological Survey of India said that Buddhism was disseminated from India to other countries mainly through trade routes. The expansion of Buddhism can more or less be mapped on the Uttarapath, the Dakshinapath, the Silk Route and the maritime trading lanes.

The notion that Buddhism first arrived in Sri Lanka in 3rd Century BC, during the rule of Emperor Dharmasoka in India, can no longer be accepted. That date gives the impression that Sri Lanka was so backward that it had to wait for 300 years after the birth of the Buddha, to receive Buddhism. It was left to King Dharmasoka to send Buddhism into Sri Lanka. Until then, it appears, Sri Lanka, despite its close proximity to India, had not heard of Buddhism. This ridiculous idea was probably developed during British rule when the Sinhala intelligentsia was persuaded that everything in Sri Lanka came to it from India. Sri Lanka could only imitate, it was not capable of acquiring anything on its own.

The reality is different. Anuradhapura was capable of accepting Buddhism during the lifetime of the Buddha. There was an advanced civilization in Anuradhapura by 900 BC. High-quality pottery, iron tools, and copper artifacts emerged during excavation. Findings indicate that there was the cultivation of rice and the breeding of cattle and horses. The writing was found at the Citadel excavation in Anuradhapura at the level dated to 900BC. Anuradhapura was therefore in a position to accept Buddhism as it emerged in north India.

Buddhism would have come into the island in the lifetime of Gautama Buddha itself. There is evidence to suggest this and many scholars have independently put forward this view. Gunapala Malalasekera in his Pali Literature of Ceylon, (1928) said there exists evidence to indicate that Buddhism was known before the arrival of Mahinda. Buddhism would have come in during Buddha’s time. Sri Lanka was a very cultured community during the time of the Buddha, he said.

E.W. Adikaram in his Early History of Buddhism (1946) also said that Buddhism existed in Ceylon before the arrival of Mahinda. Large numbers of persons were arriving from India long before Mahinda, it is difficult to believe that there were no Buddhists among them, he said. Almost every religious sect from India, such as Jains and Ajivakas were found in Pre Mahindian Ceylon. Ajivakas were not as numerous in India as Buddhists, so Buddhists probably came too, said Adikaram.

Adikaram said there may have been Buddhists among the early settlers such as Yaksha and Naga, as well. Baddhacachhana who arrived in Ceylon with her retinue was the youngest daughter of Pandu, a cousin of Gautama Buddha. They may have been followers of the Buddha, he added.

Mahiyangana stupa existed before the arrival of Mahinda. it was set up during the Buddha’s first visit. This could mean that long before Mahinda there were at least a few Buddhist monks in Ceylon and this chetiya was built by them, said Adikaram. There may have been some Buddhist missionaries from India before Mahinda. See how rapidly the conversion took place with Mahinda. After the very first discourse, 40,000 converted, observed Adikaram and several were ready to take up robes.

Adikaram took the view that Arahat Mahinda came to set up the monastic order, not to introduce Buddhism. Mahinda came to formalize the monastic order and establish the Sasana in the island. Buddhism became a state religion after that, he said. Mahinda’s mission to Sri Lanka consisted of five fully ordained monks, a novice, and one male layperson, said Ven. Wimalaratana.

Historians now agree that the meeting between Mahinda and King Devanampiyatissa was pre-arranged. That is obvious and historians should have realized this long ago. Dharmasoka had sent coronation robes to Devanam piyatissa. This shows that diplomatic relations had been established earlier between the two countries.

The Sinhalese had no difficulty in understanding Arahat Mahinda’s preaching. The Magadhi language, which Mahinda spoke, would have been similar to Sinhala. The Asokan inscriptions are similar to Sinhala inscriptions of 3rd century BC, said Adikaram.

Ven. Walpola Rahula in his History of Buddhism (1956) took the view that Sri Lanka would have known about Buddhism during the time of the Buddha himself since there was regular contact between India and Sri Lanka during that period. S Paranavitana, in his Inscriptions of Ceylon (1970) also thought that Buddhism may have come into Ceylon before Asoka.

When this writer, (Kamalika Pieris), was researching on the ancient period, she found that the research literature clearly showed extensive contact between the Ganges region of northeast India and Sri Lanka, in the critical 6 century BC period. Early Historic Period deposits of northern black polished ware and rouletted ware were found at Abhayagiri and Jetavana and at monastic sites in the hinterland of Anuradhapura. This indicated links to northern India.

Further, people were migrating freely from Bengal to Sri Lanka during this period. According to Pliny, it took just twenty days to sail from Sri Lanka to Magadha. C.W. Nicholas (1958) stated that up to 3rd century BC Sri Lankans had shown expert skill and a great tradition of seafaring. Many voyages were made to and from the deltas of the Indus and the Ganges, he said.

There was a direct trade route between Anuradhapura and Tamralipti at the time. Tamralipti, (today Tamluk, in Kidnaper, West Bengal) was the main port from northeast India to Sri Lanka during this period. North India had two major trans-regional trade routes at this time. Uttarapath for the north and north-west and Dakshinapath for the center and south. Dakshinapath crossed the Indo-Gangetic plain and ended at the port of Tamralipti in the Bay of Bengal.

Tamralipti was the main port of the kingdom of Magadha. Tamralipti was connected to the other Buddhist republics adjoining Magadha, as well, since the Uttarapata, the great Northern road, included towns such as Pataliputra, Kausambi, and Taxila. Therefore Tamralipti was well placed to act as the port of embarkation for Buddhist teachings.

There was so much movement between northeast India and Sri Lanka in the time of the Buddha that it became clear to me that Buddhism would have come into Sri Lanka as soon as it appeared in India. Buddhism simply HAD to come into Sri Lanka soon after it took root in north India. This could not be avoided. Sri Lanka would probably have had links with the various Buddhist kingdoms in the Ganges area as well.

In the 1990s, when I was researching this, I did not have any archaeological evidence to support my conclusion. The first material evidence supporting this surfaced in 1984 when the Anuradhapura Citadel excavations yielded Ganges Valley pottery with dates that ‘matched that of Gautama Buddha.’ Anuradhapura excavations unearthed a pot dated to 600-500 BC carrying Brahmi writing signifying ownership. This has pushed the lower boundary of writing by at least two centuries, to the times of the Buddha, said Siran Deraniyagala.

Speaking on these findings at a talk given to the British Scholars Association in 2007, Siran Deraniyagala stated that Buddhism may have come into Sri Lanka then. In July 2015 at a talk, held at the Organization of Professional Associations auditorium, Siran Deraniyagala again said that he thought Buddhism had come in during the time of the Buddha, long before Mahinda. That would have been Dhamma in real-time, received while the Buddha was alive and preaching in India. [1] (Continued)

[1] Siran Deraniyagala. Origins of civilization in Sri Lanka”. Talk was given to British Scholars Assoc on 6.11.07.