A study of Contemporary Buddhist-Muslim Relations in Sri Lanka Part 2

Posted on September 27th, 2017

by Prof. G. H. Peiris

August 27, 2017

Continued from Part 1

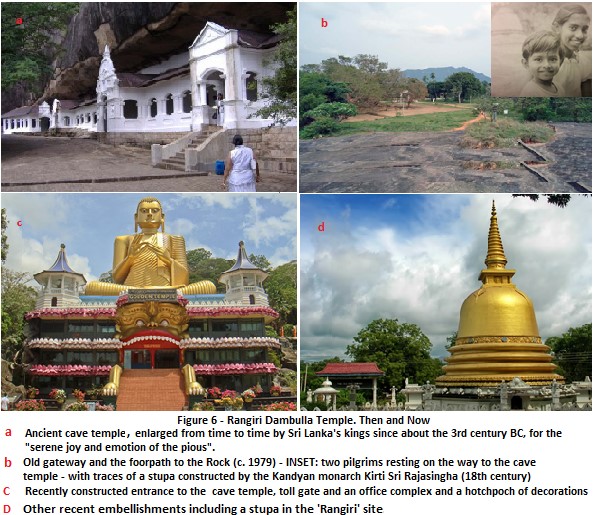

Until recent times, ‘trading’ in the vicinity of the Rangiri temple was confined to the ramshackle ‘Rest House’ (the only tavern in the town) and a few squatter stalls vending bunis, saruvath and vadai to the occasional busload of local pilgrims. The numerically tiny Muslim community of Dambulla was largely confined to its small bajār (bazaar) about a kilometre to the north of the Rangiri temple, their spiritual needs being met by a small shed located almost at the doorstep of the ancient the temple. This was private property owned by a Moslem family. According to Sinhalese residents in the temple locality at present (a fact confirmed by a former Member of Parliament for Dambulla) a few Islamic devotees had used it for ‘Friday prayers’ more or less regularly “from the time we remember”. Neither this innocuous practice nor the sundown “middle-class” boozing at the Rest House (located adjacent to the embryonic mosque) were causes for any Buddhistic concern. This “inclusivism”, it seems, lasted only until the onset of demographic transformations that accompanied the rapid commercial growth of Dambulla referred to above.

The relevance of the foregoing sketch to the political disturbances in this area stemmed mainly from the fact that the vast tracts of land which the Dambulla temple had received (pooja bhoomi, a term translated as

P’sacred land’ or ‘offered land’)[i] over the past millennia, much of it uncharted and/or uninhabited and acknowledged vaguely as Vihāragam (temple land), acquired a sharp upsurge of commercial value in the real-estate market. The first major outbreak of intense political dispute rooted in this fact was the agitation against the construction of a luxury tourist hotel overlooking the Kandalama lake ̶ a campaign which, according to a Reuter report of that time, attracted at its zenith more than 10,000 protesters (including a few volunteers for self-immolation!), objecting to the hotel project on grounds of its adverse ecological, social and cultural impact, and because it also involved a “land grab” of

Viharagam by a consortium of large commercial firms. The protest fizzled out, and an elegant hotel pioneering eco-tourism in Sri Lanka came into being, the main reason for the former (end of the protest), and the principle beneficiaries of the latter (tourist hotel) being the coffers of the Dambulla temple and Ven. Ināmaluvē Sri Sumangala whose go-ahead for the hotel project, it was widely rumoured, was purchased by the investors for a large sum of money.

A similar windfall for the temple coffers is said to have occurred in the negotiations that led to the lease of land to the International Cricket Stadium of Dambulla. An article by D. B. S. Jeyaraj (journalist well-known as a virulent critic of many Sri Lankan affairs) refers to the Cricket Board Chairman confiding to a colleague that the Dambulla prelate is demanding a “king’s ransom” as a payment for the lease.[ii] The other ‘give-and-take’ transactions that also provided satisfaction to all concerned including the peasantry of the area was an undertaking fulfilled in part) that their youth will be trained and recruited to the hotel workforce. Needless to stress, these also meant an enormous enhancement of Sri Sumangala Thero’s status as a folk hero of the area whom many kowtowed and obeyed. The prelate, according to a highly knowledgeable informant, took steps some years ago to form a “sub-chapter” named the Dambulu Pārshavaya within the ‘Asgiriya Chapter’ (of the Siyam Nikāya) which traditionally exercises overall custodianship of many Rajamaha Vihāra (ancient “Kings’ Temples”) of Sri Lanka.[iii] My references here to Ven. Sri Sumangala as the ‘prelate’ could be an error from statutory perspectives. It has recently transpired that the real Vihārādhipathy (chief incumbent) of the Dambulla temple, as appointed by the Asgiriya Chapter, is Godagama Mangala Thero. If this is judicially substantiated it would have potentially far-reaching thematic implications to the present study.

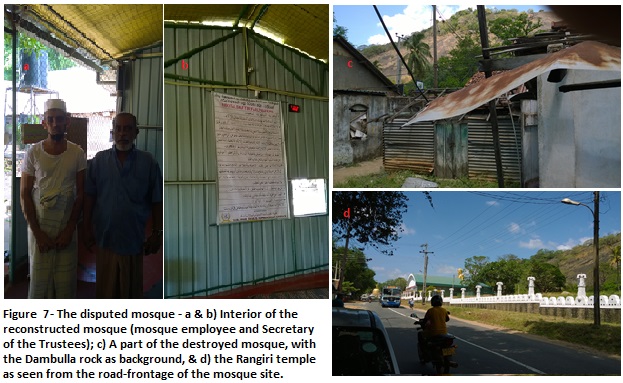

A realistic understanding of this setting, instead of being led by a fixation on the image of Buddhist bigotry and Sinhalese triumphalism (which, of course, is what rings a bell in the ‘liberal’ West) is necessary to grasp the realities pertaining to the mosque dispute. There was no demolition of a mosque despite its ill-conceived location almost at the doorstep of the Rangiri Dambulla shrine complex. Since the repair of minor acts of vandalism in its precincts caused on 20 April 2012 within a couple of weeks, the mosque has continued to be used by the Moslems of the township uninterrupted and, according to the Secretary of its Board of Trustees interviewed by me, despite an unfulfilled government promise of a more suitable site being found for a mosque within the Dambulla town.

What provoked the ‘Prayer Room’ attack? Was it the culmination of a gathering storm produced by the local ‘cultural’ transformations, or was it part and parcel of an externally manipulated political plot? Speculating on the basis of information obtained from a wide variety of sources I am inclined towards the view that, as in the other ethnic flashpoints such as Mahiyangana, Grandpass and Aluthgama, here was a scenario of coalescence of the extraordinarily rapid socioeconomic transformation in the Dambulla area which the external destabilising forces mobilised in order to attain their larger political objectives.

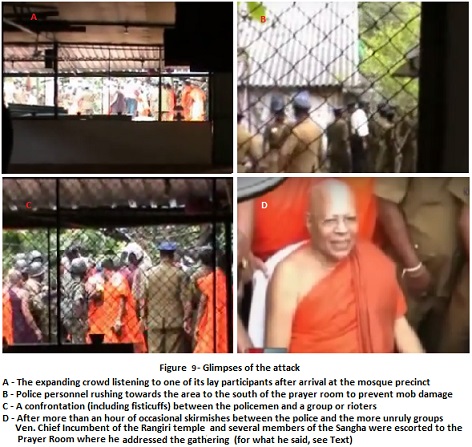

To begin with, we should re-examine the core of this tragic episode ̶ events at the venue of the disputed mosque site on Friday, 20 April 2012. The “truth” disseminated worldwide was that a massive mob of Buddhist monks and laity led by Ven. Ināmaluwē Sri Sumangala engaged in a barbaric attack on the mosque, facing no restriction from law enforcement authorities. A report filed by the BBC correspondent, Charles Haviland, the same day from Colombo spiced it with a passing mention of a “fire-bomb” attack on the mosque the previous night (this is denied by the mosque trustees) and “a monk was seen exposing himself against the mosque as an insult” (surely, the imagination of a sexual deviant!). Almost all media reports and features since that time have also referred to the “destruction”/”demolition”/”removal” of the mosque as an outcome of the attack, using the past tense to refer to the mosque in order to indicate that the ‘Haima Jumma Masjid’ in Dambulla is no more. This, of course, is something any scholar like John Holt who has been around here for more than thirty years could have verified with a two-hour drive from Kandy along one of the more pleasant highways in the country.

Since the entire attack had been filmed from inside the Prayer Room by one of its devotees, there is adequate photographic evidence to indicate that the alleged “destruction”/”demolition” is a lie. The persistence with this falsehood cannot be attributed to sensational reporting. It is deliberate political strategy, highly successful in its objective of initiating the alienation of the Muslims throughout the island from the Rajapaksa regime.

The only segment what I have referred above as the “widely disseminated truth” is that a large crowd led by Ven. Sri Sumangala arrived at the premises of the disputed mosque in a display of potential for mob violence, refraining however from converting that potential to a rampage. The ‘Prayer Room’ (about 1,000 sq. feet of floor space) that had all along served as the ‘Haima Jumma Masjid’ was left untouched. A part of the mob did cause some damage to a dilapidated and abandoned structure standing adjacent to the Prayer Room.

What is perhaps more depressing than all else in this so-called “demolition of the mosque” episode is the statement made by Ven. Sri Sumangala (Fig. 9 D) in the presence of a gathering of bhikkus, police officers and lay community leaders who were permitted to enter the mosque towards the end of that day’s proceedings, in the course of which he threatened: “What you have seen is only a peaceful demonstration, we carried only flags and placards; next Monday it will be quite different”. That enactment of violence did not happen. What did happen two days later was an announcement by the Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne that the government has decided to facilitate the establishment of an Islamic place of worship at a more appropriate site. The BBC report filed from Colombo on the 12th of April, however, was titled “Sri Lanka Government Orders the Removal of the Dambulla Mosque”. It made no mention of the cordial discussion held between Ven. Sri Sumangala and several respected elders of the Muslim community in Dambulla led by Al-Haj Maulavi Kaleel attempting to reach a compromise on the spiritual need of the local Muslim community without violating Buddhist sensitivities. A filmed recording of this discussion indicates the Muslim delegates making a passionate appeal for the prelate’s intervention to obtain from the government a suitable site in Dambulla for a mosque, and Ven. Sri Sumangala’s non-committal response that stated: “I am only a leader of my religion, I have no power over secular matters”.

The Muslim leadership at the national-level (barring a few exceptions but including the stalwarts in mainstream politics) was thoroughly hostile towards any attempt at reconciliation. While Al-Haj Kaleel was condemned with the damning the charge that he is not a genuine Muslim, the other participants of the discussion were accused of acting without authority to represent the Muslims. On 25th April the Chairman of the ‘All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama’ declared that such a relocation of the mosque is not an acceptable option, while the prelate Sri Sumangala reverted to his insistence that the mosque must go.

Any dispassionate observer of these events should accord a place of honour among the few religious leaders of the country who made sustained efforts to pacify the anger among the Muslims in other areas of the country provoked by the flood of hyperbole and half-truths. The available records also indicate that from the Muslim side the widening chasm Maulavi Kaleel and a few other Islamic dignitaries addressed a series of meetings in localities such as Grandpass, Akurana, Hemmathagama and Mawanella that are features by numerically large Muslim communities, appealing for peace and providing unqualified support for ‘National unity’ among all Sri Lankans.

Throughout that week of uncertainty and country-wide Muslim protests, the mosque was kept under formidable police protection; and a permanent police-post manned round the clock, established at the mosque site, has been functioning up to the present. The ‘truce’ appears to have lasted, now more than 5 years. One of the cops, quite bored with his guard duty, with whom I had a chat said: “No, there is no trouble at all”.

According to the secretary of the Board of Trustees of the mosque, Mr S. H. M. Rauf, following that week, Friday devotional rituals have been conducted at the mosque regularly and undisturbed ever since, with a growing number of Islamic devotees. While reiterating that the Muslims “will never agree to shift the mosque from the present site”, he disclosed that: (a) the present 40-perch block of land is owned by the mosque trustees on the basis of a clear title deed; (b) the venue includes an allotment purchased by the trustees in 1995 for future expansion (presumably, this addition is the extent occupied by the “dilapidated structure” shown on Figure 7 C, (p. 17 above); (c) the mosque established in the 1960s, despite its inadequacy of space, fulfils an essential need of the expanding Muslim population in Dambulla;[iv] and (d) the Muslims see a vicious contradiction in the objection to the mosque on the basis of the sacred ‘Pooja Bhoomi‘ claim, while disregarding the fact that land adjacent to the highway on the mosque-side has been occupied, in some cases over many decades, for profane uses such as surāmērayamajja pamādatthānā at the ‘Rest House’ (a use now officially prohibited, I was told), not to mention the other ‘inviolables’.

My field investigations indicate the presence of a general acknowledgement among devout Buddhists in Dambulla of Ven. Sri Sumangala’s extraordinary fund-raising accomplishments. This has, in fact, found confirmation in a recent statement attributed to the present Minister of Education, Akila Kariyawasam, according to which an investigation conducted by the Commissioner of the ‘Central Cultural Fund’ has revealed the annual income of the Dambulla temple from entrance fees alone (thanks to the Makara Thorana through which the visitors need to pass) ranging between 7 billion to 15 billion rupees (roughly, US$ 50 to 100 million).[v] Despite the cynicism, many educated Buddhists agree with the prelate’s standpoint in that they endorse the notion of localities around ancient Buddhist shrines deserving to be statutorily declared ‘sacrosanct’ as integral components of the nation’s treasured heritage. They argue (quite correctly) that large extents of Vihāragam were grabbed by the colonial government from temple ownership through various land ordinances[vi] and transferred to secular uses. It is of interest that the plot of land belonging to the disputed mosque was purchased from an Englishman in the 1950s by a person from Jaffna from whom a Muslim trader bought it and donated it to the mosque trustees. There is also the frequently raised rhetoric by Buddhists: “Would Islamic or Christian countries permit shrines of other faiths to be constructed adjacent to their major places of worship? I add to this my own conviction that the project which involved the conversion of the old township of Anuradhapura to a ‘Sacred Buddhist City’ (alongside the construction of a secular ‘New Town’ in its periphery) launched, it should be remembered with gratitude, during the penultimate phase of British rule over ‘Ceylon’, presents a model that should be emulated elsewhere in several other places, maybe on a smaller scale. It is an urgent ‘must’ in Kandy.

There is a tailpiece to the story of the “Dambulla Mosque Demolition” captured by the ‘Derana‘ TV crew that makes it possible for us to leave the township with a tentative sigh of relief about the fact that bigotry did not remain entirely unchallenged under the very shadow of the ancient shrine (Figure 11). At the end of the attack, after the mosque had been locked up and sealed under government orders, Ven. Sri Sumangala was escorted out to the highway on his return to the temple by a police contingent. A woman who, along with about ten others, had waited in their home garden adjacent to the mosque, stepped out boldly and confronted the monk with a respectful but firm statement that she has been living there since her childhood, and it would be unfair for those who have been in the locality all their lives to be harassed. What is distinct from the prelate’s increasingly irritated responses (TV sound track, not very clear) was, “in earlier times crows merely flew above our heads, but now they have started to build nests on our heads.” (Sinhala term for crows – kākko – is said to be a derogatory reference to Muslims). Referring to the house from which the woman had come out as a kōvil (Hindu shrine), he also said that they should all go elsewhere. The monk was saved further embarrassment by the police who ordered the woman to give way.

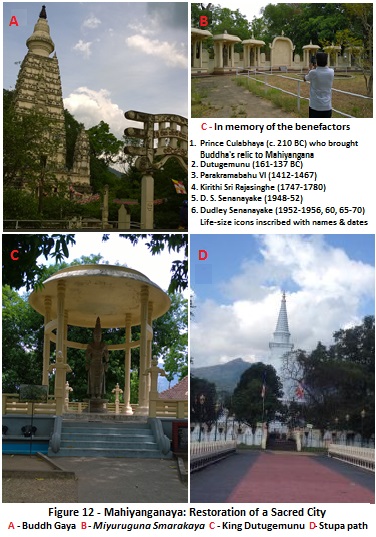

Mahiyangana: Sacred and Profane

Mahiyangana has an almost unique significance for Sinhalese-Buddhists. It is based partly on their belief that it has been sanctified by Buddha’s first visit to the island, and its stūpa in its original form was erected to enshrine Buddha’s collar-bone brought there within about a decade of Arahat Mahinda’s mission in Sri Lanka (c. 3rd Century BC). It is also attributable to their treasured memory that until about the end of the 12th century

Mahiyangana served as a strategic township in various military encounters between Rajarata and Ruhuna, especially those of the chronicled national heroes like Dutugæmunu, Keerthi Vijayabāhu and Mahā Parākramabāhu. These, more than all else, are the reasons for Mahiyangana receiving very special attention in post-independence ‘resurgent’ endeavours of the Sinhalese-Buddhists.

There was, first, the restoration of the Mahiyangana stūpa pioneered by the then Minister of Agriculture and Land, D. S. Senanayake, in 1942 probably in recompense for about 1,000 acres of viharagam he acquired from the temple for the ‘Minipé Peasant Settlement Scheme’, one of the earliest of its kind in the drier parts of the country.[vii] Yet until the mid-1980s Mahiyangana remained a small market town catering to the modest needs of the peasantry of its hinterland and the trickle of pilgrims from the highlands venturing down the precipitous ‘eighteen hairpin bends’ in ramshackle buses.

The real impulse for urban development in the Mahiyangana locality was generated by the opening up of nearly 25,000 hectares (62,000 acres) for irrigated agriculture in ‘System C’ of the Mahaveli Development Programme (MDP) from about the mid-1980s to the early ’90, and the consequent migration into what had earlier been degraded forest and scrubland an estimated 28,000 family units, the large majority among them producing a surplus of paddy, but dependent on external sources for most of their other needs in goods and services. The town in Mahiyangana, located at the gateway to ‘System C’ (and, dynamic areas beyond that – the larger peasant settlements in ‘System B’ of the MDP opened up in the more recent past, and the rich farmlands of the Polonnaruwa District – thus emerged as the foremost urban centre of the plains bordering the Central Highlands to the north-east.

For well over 35 years after the Senanayakes, father and son, had completed the restoration of the historic stūpa, nothing significant occurred in Mahiyangana by way of further improvement of Buddhist shrines. Thus it was only in the late 1980s when Ranasinghe Premadasa took over the reins of government that Mahiyangana became what in retrospect could be seen as the venue of the largest ‘Sacred-City’ development project in post-independence Sri Lanka. Some of the initial components of the project were implemented in anticipation of his Gam Udāwa (“Village Awakening”) annual tamasha of 1989. These included the installation, adjacent to the western entrance to Mahiyangana, a replica of the shrine at Gayā, the birthplace of the Buddha (Figure 12 A), and a monument named Miyuguna Smārakaya in memory of past patrons of the town (Figure 12 B), beautifying several smaller Buddhist shrines such as Poorvārāmaya and Sangamitta Ārāmaya, and a face-lift of the ‘sacred area’ around the Rajamaha Vihāraya which included the renovation of the Saman Dēvālaya (shrine of Sri Lanka’s guardian deity, said to be as old as the stūpa), in addition to widening the streets, and upgrading the hospital and the secondary school.

( to be continued Part 3)

[i] . A report compiled by G. M. Abeysekera, Senior Superintendent of Surveys, Sri Lanka show that the

Commission appointed to implement the ‘Temple Lands Registration Ordinance of 1856’, settled a total extent of 23,044 acres in 17 blocks ranging in size from less than an acre to 12,636 acres (venue of 11 villages) were “settled” in favour of the Dambulla Temple.

[ii] . Jeyaraj, D B S (undated) ‘Rangiri Cricket Stadium and Its Tempestuous History’, in

Dbsjeyaraj.com/dbsj/archives/6004

[iii] . See also, http://www.goldentemple.lk/Backup/2016-10-01/development_foundation, for a further reference to this new “Chapter”.

[iv] . Yusuf, Javid (2012) ‘Immediate investigation needed for Dambulla Mosque incident’, It has been posted in the blog dbsjeyaraj.com/dbs/archives/5906 on 28 April 2012 – i.e. eight days after the mosque attack.

[v] . See the full-page record of an interview with the minister by Piyasena Dissanayake & Nilantha Madurawala in Irida Divayina (Sunday issue of a national newspaper) of 9 July, 2017, page 13.

[vi] . Peiris G. H. (1981) ‘Agrarian Transformations in British Sri Lanka’, Sri Lanka Journal of Agrarian Studies, 2(2): 1-26.

[vii] . Peiris G. H. (1987) Irrigation and Water Management in a Peasant Settlement Scheme of Sri Lanka, Agrarian Research and Training Institute, Colombo: 18-24.