THE TRUE COST OF AUSTERITY AND INEQUALITY

Posted on April 14th, 2022

Greece Case Study OXFAM CASE STUDY

Among EU nations, Greece has been hardest hit by the impact of the

financial crisis. Two years ago, in June 2011, The Economist evaluated

the EU‟s actions towards Greece and said that a new rule seemed to

have been adopted: „if a plan doesn‟t work, stick to it‟.1 Two years later

there is no sign of any change in direction, while the social and political

situation continues to worsen.

Context of the crisis in Greece

In Greece, the decade leading up to the crisis was characterized by a

lack of structural reform in taxation, public debt and public sector pay.

Greece had a poorly organized fiscal system, defective social services,

and political parties that failed to agree on how these should be

reformed.

In October 2011, it was revealed that 109,421 people who did not appear

in the census were, however, receiving state pensions from the main

social security fund. It was estimated that the total amount paid out to

these fake pensioners could have been as such as €1.5bn. In June 2011,

the International Monetary Fund (IMF) declared Greece‟s fiscal system a

shambles, noting that the problem arose from a lack of political will,

which exacerbated a lack of competitiveness and economic isolation.2

The lack of any increase in tax revenues, set against rising government

benefits and consumption, revealed severe shortcomings in the Greek

tax system. One of the primary deficiencies was the tax authority‟s failure

to collect taxes: tax evasion in Greece may have reached as high as 27.5

per cent of GDP in the period 1999 to 2007 – amounting to the largest

informal economy of any EU country.3 Former Finance Minister

Evangelos Venizelos complained in 2011 that only 25,000 Greeks

declared an annual income of more than €100,000 and barely 160,000

admitted to earning more than €50,000. Fraud control was clearly

lacking.4 Mr Venizelos said that changing the situation was both an

economic priority and a moral obligation. Self-employed workers

represented 37 per cent of the Greek workforce, compared to an average

of 15 per cent in the EU overall. Being self-employed was very appealing,

as the taxes paid by this group in Greece were about 15 per cent (the EU

average rate was nearer 25 per cent) and, with so few taxes being

collected, the freelance worker had greater opportunities for fraud.

Greece maintained a public debt of around 100 per cent of GDP during

the decade prior to the crisis, which is 20 to 30 per cent more than other

comparable countries.

An important area in which Greece failed to reform before the crisis was

public sector pay. From the early 1990s onwards, the gap between public

sector and private sector pay widened dramatically. By 2011, it was

estimated that public sector salaries were 130 per cent higher than those

of private employees, while the average difference across the Eurozone

was 30 per cent.

Salaries for workers in similar categories were much

higher in the public sector, creating a system of „insiders‟ and „outsiders‟.

This, together with the failure to collect taxes, partly accounts for the

increase in Greece‟s public debt.6 No governing party (neither the

Panhellenic Socialist Movement, PASOK, from 1993 to 2004, nor the

conservative New Democracy, ND, from 2004 to 2009) managed to carry

out the reforms needed to correct the situation before the crisis hit.

The rescue package and austerity measures

When the crisis struck, the PASOK government (re-elected in June 2009)

agreed to enact the economic plans imposed by the EU, the European

Central Bank and the IMF, laid out in their 2010 Memorandum.7

In return

this group, known as the Troika, provided loans which allowed Greece to

avoid defaulting on its debts and going bankrupt. The following are some

of the reforms demanded by the Troika:

• Cuts in public sector salaries: A freeze on public sector salaries

until 2014; the immediate cut of two of the 14 monthly salary

payments in the public sector for those employees with a salary above

€3,000 per month, and a reduction of the 13th and 14th payments for

those who earn less than €3,000 per month. A recent IMF report,

however, said that reform of the excessive number of public sector

positions has largely been pushed aside due to reluctance to lay-off

employees.8

• Pension reform: A reduction of up to 26.4 per cent in payments to

pensioners and a rise in the retirement age to 65 years for women and

men; a penalty of six per cent for early retirement.9

In September 2012

the retirement age was further raised to 67.10

• Tax: The government was supposed to introduce a new plan to

improve tax collection, reduce capital flight and fight tax evasion. The

IMF maintains that very little progress has been made on obvious tax

evasion11 and neither the rich nor the self-employed have yet to begin

paying their dues.12 Unfortunately, VAT – a far more regressive route

to raising tax revenue that tends to penalize low-income groups – was

raised 10 percentage points across all categories.

In April and May 2010, various tax system reforms were launched: bank

bonuses and financial services would henceforth be taxed up to 90 per

cent, and property taxes were tripled for foreigners with a summer

residence in the country.13 Cash payments of more than €1,500 were

prohibited, in order to limit fraud, and people who provided information on

tax cheats were rewarded with 10 per cent of the amount recovered by

the authorities. For the self-employed earning more than €40,000

annually, the tax rate went from five to 40 per cent. Any household with

an annual income above €100,000 would pay a new top-rate tax of 45

per cent, representing a five per cent increase. Only those whose income

was €25,000 annually or less would not be subject to a tax increase.14

Unfortunately, the tax control measures have not brought the anticipated

results. Finance Minister Giorgos Mavraganis was asked why the

government had only collected €14m of the €9.7bn owed by the biggest

tax debtors (the total accumulated amount lost through tax avoidance is

actually €52.3bn).15 He admitted that Greece had only collected that sum

(0.0014 per cent of the amount owed), but said that this was due to many

companies going out of business and people using false invoices to

deflect inspectors.16 El País reported on 24 May 2011 that capital flight

was intensifying, leaving Greece on the verge of bankruptcy. The

newspaper said that Greeks held €280bn in Swiss bank accounts, the

equivalent of 120 per cent of Greece‟s GDP.17

Against this backdrop was the constant pressure from Greece‟s huge

public debt. Already high, this saw a dramatic increase following the

Troika‟s rescue package, at twice the rate of comparable countries.

As a result of the economic problems faced by Ireland, European

governments and financial institutions tried to establish mechanisms that

would regulate country „rescue‟ deals. In the case of Greece, the decision

to approve the loans for the government had two essential features: 1) the

government had to accept direct responsibility for their repayment; and 2)

the money lent became part of the public debt. The constant increase in

Greek public debt due to the rescue package has meant that in

subsequent „rescues‟ the loan was granted to the banks (as bank loans) in

order to avoid indiscriminate increases in the level of public debt.

Greece is unlikely to maintain this debt within the limits set down by the

EU‟s Stability and Growth Pact (which originally said that all countries in

the Eurozone should aim to keep their annual budget deficit below 3 per

cent of GDP and keep total public debt below 60 per cent of GDP),

especially given that servicing the debt accounted for 13.9 per cent of

Greek public spending in 2011.

Impact of the rescue package and austerity measures

Electoral repercussions

The economic crisis has changed the terms of the Greek political system,

from left-wing and right-wing political parties to „pro‟ and „anti‟ the 2010

Memorandum and austerity measures that followed. Surprisingly, the

conservative ND party was opposed to it, while the governing PASOK

party was in favour. In May 2012, ND won a general election, after the

public showed their utter rejection of the Troika‟s austerity package. This

election marked an end to the traditional two-party system.

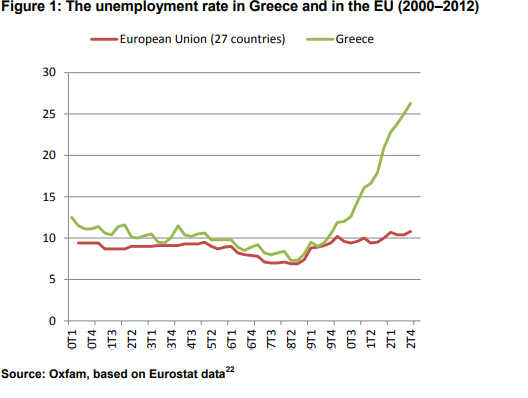

More unemployment

In 2010, household disposable income18 in Greece decreased by 12.3

per cent compared to 2009.19 This was primarily due to rising

unemployment, rather than falling salaries.20 Unemployment has

continued to rise steadily throughout 2013. Eurostat indicates that the

greatest rise in unemployment in the EU, between January 2012 and

January 2013, was in Greece, from 21.5 per cent to 27.2 per cent.21

Figure 1: The unemployment rate in Greece and in the EU (2000–2012)

Source: Oxfam, based on Eurostat data22

Poverty and inequality

Figure 2 shows how the parallel progression of Greece‟s per capita gross

national income (GNI) diverged from that of the OECD average around

the time the first rescue deal was approved in 2010.

European Union (27 countries) Greece

Figure 2: Evolution of per capita GNI in Greece and the OECD

country average (in constant $)

Source: OECD, www.oecd.org

In 2011, Greece had the highest rate of those at risk of poverty or social

exclusion in the Eurozone (31 per cent compared to an average of 24.2

per cent across the EU as a whole). This had been slowly decreasing,

but has now risen back to 2004 levels. In 2011 alone, this increased by

3.3 per cent, meaning that 372,000 more people were at risk of poverty

or social exclusion.

More than one in three Greeks fell below the poverty line in 2012 (once

figures are adjusted for inflation and using 2009 as the limit for setting the

poverty line). The middle class has shrunk and is closer to the poverty

line, while the poor are getting poorer and inequality is increasing.

Greece continues to be the only Eurozone country with no basic social

assistance system that provides a safety net of last resort.23

The suicide rate in Greece has increased 26.5 per cent from 377 in 2010

to 477 in 2011, and has increased by 104.4 per cent in the case of

women.24

Between 2001 and 2008 the number of people aged between 18 and 60

living in households with no income remained fairly constant, falling

slightly from 9.4 to 7.5 per cent. That has reversed since the beginning of

the crisis, and particularly since the introduction of the rescue package

measures, with the number of people living in households with no income

rising to over one million in 2012, equal to 17.5 per cent of the

population.25

Figure 3: Percentage of the population living in jobless households

(except households of students between 18 and 24 years old who

do not work)26

After six consecutive years of recession and four of austerity, Greek

society is becoming increasingly fragmented. The homeless population is

thought to have grown by 25 per cent since 2009, now numbering 20,000

people.27

Scant social resources and rising extremism

The public health system is increasingly less accessible, especially for

poor and marginalized groups. Close to one in three Greeks have no

public medical insurance, most often due to long-term unemployment.28

The increase in poverty and unemployment and the weakening of social

services have been accompanied by an increase in the crime rate.29

Far-right parties Golden Dawn and AnEl each achieved seven per cent of

votes in the 2012 election. Their successes can be attributed to the

country‟s grave economic situation and a drop in confidence in traditional

parties. The main strength of Golden Dawn, which blames the crisis on

non-Greeks, derives from the role it plays in some Athens

neighbourhoods with a particularly high percentage of immigrants.30

There, it has become very visible, offering to step in where the state has

failed to do so. In apparent acts of collusion with local police, Golden

Dawn has provided personal safety services for hungry pensioners who

feel too frightened to go outside.31 It offers food distribution for Greeks

only, and military-style groups savagely attacked immigrants and those

Greeks who stand up to them.32 Such groups have dedicated themselves

to hunting down immigrants who live on the street with no resources.

Human Rights Watch reports that there is a burgeoning crisis of

xenophobic violence towards immigrants and political refugees in Athens

and across the country.33 Extreme right-wing fanatics have stormed

through neighbourhoods with immigrant populations. One incident in

2011 left at least 25 people hospitalized with wounds from knifings and

serious beatings.

Conclusion

The situation in Greece today is very volatile. Austerity measures have

left a large part of the population in dire straits. Cuts in public

expenditure, coupled with constantly rising unemployment, have left

many people either destitute or close to it.

With a third of the population on the threshold of poverty and 17.5 per

cent living in households with no income, family networks can no longer

be relied on to support the needy. A fair tax system capable of combating

tax evasion is essential in order to once again fund the social protection

networks that have been incrementally dismantled during the crisis, as

part of the Troika‟s rescue deals.

But this will require decisive political action and, as Greece witnesses a

collapse of its political system, that does not appear to be a likely

prospect. The political vacuum has led, in turn, to a feeling of public

insecurity, fed in part by a rise in racism and xenophobia. If institutions, in

particular the government and the parliament, do not succeed in

regaining public trust it will be even harder to emerge from the financial

crisis. For that to happen, economic policy must put people‟s needs first.