Minimum support price(MSP) increase could hit non-basmati rice exports in India

Posted on July 14th, 2018

Written by Harish Damodaran | New Delhi |Courtesy The Indian Express

Updated: July 15, 2018 3:40:08 am

The government’s decision to raise the minimum support price (MSP) of common paddy from Rs 1,550 to Rs 1,750 per quintal this crop season may benefit farmers ahead of elections, but could impact the country’s export of non-basmati rice.

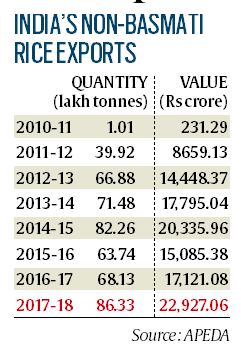

The government’s decision to raise the minimum support price (MSP) of common paddy from Rs 1,550 to Rs 1,750 per quintal this crop season may benefit farmers ahead of elections, but could impact the country’s export of non-basmati rice, annually worth almost Rs 23,000 crore.

Much of India’s non-basmati exports — which have zoomed from just one lakh tonnes to over 8.6 million tonnes (mt) in this decade — are to African nations, both West (Benin, Nigeria, Niger, Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Guinea and Senegal) and East (Somalia and Djibouti), and also to Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

These are poorer countries relative to West Asia, UK, Europe, US, Canada and Australia, the main markets for the more premium basmati rice.

In 2017-18, India shipped out 4.05 mt of basmati rice, which was less than half the quantity of non-basmati (8.63 mt), but of higher value (Rs 26,841.19 crore versus Rs 22,927.06 crore for the latter). Unlike basmati, non-basmati rice is a highly price-sensitive segment. The MSP increase will totally erode India’s price competitiveness,” said an official from a major agri-commodity exporting firm.

Currently, long-grain (6 mm) parboiled rice with 5% broken grain content – which is what India largely exports – is quoting at $385-390 per tonne free-on-board (FOB, or the point of shipment). Paddy yields roughly two-thirds rice, with the milling costs – including salaries, interest and overheads – more or less recovered from sale of husk and bran. If paddy is sourced from Chhattisgarh, Odisha or Andhra Pradesh at an MSP of Rs 1,550 per quintal, the equivalent price of milled rice will be around Rs 23.25 per kg. After adding commission fees, local levies and transport charges of Rs 1.25, the delivered cost at Kakinada port will come to Rs 24.50/kg. On top of this are fobbing costs” (towards bagging, warehousing, inspection, customs clearance and cargo handling/stevedoring) of Rs 1.50, which takes the final FOB price to Rs 26/kg or $380 per tonne at Rs 68.5-to-the-dollar.

READ | Centre’s MSP hike decision betrayal of promises made to farmers: AIKSCC

But with the new paddy MSP of Rs 1,750 per quintal, the basic rice cost itself will go up by Rs 3/kg or nearly $44 per tonne. At this rate, we will be completely priced out. Today, even long-grain white raw rice with 5% brokens from Thailand is selling at below $400 per tonne FOB,” the earlier-quoted exporter pointed out.

The implications of it aren’t small. India produces about 110 mt of rice, out of which 36-38 mt is procured by government agencies and 12.5-12.7 mt is exported. The higher MSP is not applicable on basmati paddy and would anyway make little difference to the four-mt exports of this premium rice. But to the extent the 8.5-8.7 mt of non-basmati rice exports are affected, there will be that much of surplus grain in the domestic market, which may end up in government warehouses. This, when public rice stocks, at 23.25 mt as on July 1, are way above the normative buffer of 13.54 mt required to be maintained before the start of the new agricultural year.

ALSO READ | MSP hike: Farmers yet to reap gains on the ground

The entire 8.5-8.7 mt exports may not take a hit, but at least 3 mt or so can be impacted. The two offsetting factors could be a further depreciation of the rupee and a bumping up of prices by Indian exporters,” noted Ashok Gulati, agriculture economist and former chairman of the Commission for Agricultural Costs & Prices.

India, according to US Department of Agriculture data, accounted for 12.8 mt out of the total global rice trade of 48.98 mt in 2017-18, making it the world’s largest exporter, ahead of Thailand (10.5 mt), Vietnam (7 mt), Pakistan (4.2 mt), Myanmar (3.5 mt) and the US (3.05 mt). Being a large exporter, India can set prices. But the ability to pass on the higher MSP is limited by the low purchasing power, especially of African countries who may even switch to cheaper cereal substitutes like cassava. Besides, Thailand and Vietnam may respond by ramping up their supplies and grabbing our market share,” added Gulati.

But there could also be a third possibility – of rice meant for the public distribution system (PDS) getting diverted for exports. This, if trade sources are to be believed, is already taking place. Given that the Central issue price for rice under the National Food Security Act is just Rs 3/kg – states like AP, Telangana, Odisha and Chhattisgarh are offering it at Rs 1/kg – the incentives for diversion are obviously huge.

PDS rice typically has 20-25 % brokens. There are traders/millers who manage to get these through collusion with food department officials and transporters, which they then convert into 5% brokens (by adding unbroken or head rice bought from the market) and sortex (to remove discoloured and damaged grain) for achieving export quality,” explained an exporter, who, however, couldn’t quantify the extent of such PDS-diverted shipments.

Leading non-basmati exporters from India include the Singapore-based Olam International and also not-so-well-known domestic players such as Satyam Balajee Rice Industries, Pattabhi Agro Foods, HRMM Agro Overseas, Amir Chand Jagdish Kumar Exports and Sukhbir Agro Energy.