Prehistoric community heterogeneous despite Sinhalese character and ethnos

Posted on January 15th, 2022

By Seneka Abeyratne Courtesy The Island

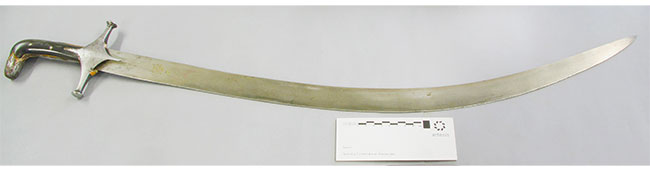

Kozakian Shamshir weapon made of crucible steel from the collection of the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History, Brussels

The ancient kings, inspired by Buddhism and the constant need to feed a growing population, produced a new culture as well as a new economy. They also created the necessary institutions to plan and implement development projects for transforming the dry zone. Buddhism figured prominently in the island’s hydraulic civilization, which emerged during the Early Historic Period (500 BCE-300 CE). Although the irrigation bureaucracy was highly centralised, it produced results. There was a steady increase in agricultural production which kept pace with population growth and also stimulated technological change in the non-farm sectors through backward linkages.

However, there were occasional famines caused by various factors including invasions, internal strife, and adverse weather conditions. These famines occurred over a period of fifteen centuries in both the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa kingdoms. Hence, despite the development of an intricate irrigation system in the dry zone, the uncertainty of food production always remained (Siriweera, W.I. History of Sri Lanka: From earliest times up to the sixteenth century, second edition, 2004).

Dual role of monastic complexes

The vibrant Buddhist culture also produced a flowering of religious art, architecture, and sculpture and a proliferation of the arts and crafts. Owing to its pivotal position in the ancient maritime silk route, the island would no doubt have benefited from winds of change blowing from East and West.

The Buddhist monasteries were heavily patronised by the royalty and served as key intermediaries between the monarchs and the rural people. The monastic complexes owned large extents of land, irrigation works, dairy cows, and draft animals. The manpower they had in their service consisted mainly of agricultural labourers and artisans. The latter included carpenters, wood-carvers, potters, brick-makers, and blacksmiths. The complexes possessed a range of implements for use by the skilled and unskilled workers. Consequently, they functioned not only as places of worship but also as key resource centres.

What is still more significant is the role of the monastery in promoting different crafts including iron-smelting and metal craft. It adds another dimension to the multi-faceted activities in which these institutions had been involved” (Karunatilaka, P.V.B. Metals and Metal Use in Ancient Sri Lanka, 1991-92). Consequently, the larger monasteries, in addition to performing religious duties, engaged in diverse economic activities. By promoting metal crafts using hands-on training methods, they also served as agents of technical change.

Steel manufacturing

As we saw, iron and steel implements of superior quality were being produced in the island during the Early Historical Period. Numerous archaeological studies suggest that India and Sri Lanka were the first two countries in the world to produce and export wootz – a hard, durable, high-carbon steel. Both countries exported wootz steel to the Middle East. While in India, the iron-smelting furnaces for producing wootz steel (also known as crucible steel) were charcoal-fired, in Sri Lanka, they were wind-powered. This method of producing wootz steel was unique to the island. The ancient, wind-powered furnaces were built in the Samanalawewa area (located in the southern foothills of the central highlands), where there was an abundant supply of iron ore (Juleff, G. An ancient wind-powered iron-smelting technology in Sri Lanka, 1996). These remarkable structures have been dated to 300 BCE using radiocarbon dating techniques (Hewageegana, P. Early Iron and Steel Production in Sri Lanka: A Scientific Perspective, 2014).

During the first millennium CE, steel manufacturing developed into a major ferrous metallurgy industry in South Asia. The legendary Damascus swords, noted for their strength and sharpness, were produced from ingots of wootz steel imported from India and Sri Lanka. It was the Arabs who introduced this quality product to Syria.

The Sunday Times reported more than a decade ago that Gill Juleff (a British archaeologist) was in the process of establishing a full-scale model of the Samanalawewa wind-powered furnace at the Martin Wickramasinghe museum in Koggala (Sadanandan, Renuka, Blowing back to a red-hot history, The Sunday Times, August 31, 2008). Her excavations, carried out in Samanalawewa over a two-year period (1990-91), revealed that each site had several furnaces. Juleff discovered a total of 77 sites in Samanalawewa with furnace remains, all of them located in the path of monsoon winds on the western margins of hills and ridges. Perhaps the Chola invasions led to the collapse of this large-scale metallurgy industry in the 11th Century.

Megalithic culture

It appears the 3rd century BCE on the whole was a vibrant period of Sri Lanka’s ancient history when various factors (both exogenous and endogenous) converged to produce a flowering of the island’s famed Early Iron Age megalithic culture. Archaeological research, which commenced during the British colonial period and is continuing to probe the island’s ancient past, has demonstrated a clear biological connection or continuum, if you will, between the prehistoric and historic peoples. Similarly, haematological and genetic investigations suggest that the ethnic mix of Sri Lanka’s population is quite consistent with the island’s geographical location. Though the island lies between South India and Southeast Asia, it is geographically much closer to the former than the latter. It is not surprising therefore that the ethnic mix is weighted towards southern India.

There is no solid evidence to indicate that the early Sri Lankans were a homogeneous migrant group. What the available data suggest, on the other hand, is that the Sri Lankans were no less heterogeneous in the prehistoric past than they are today. This island, though relatively small, is exceedingly complex in respect of its social, cultural and demographic characteristics due to its long history of human habitation.

The megalithic monuments scattered throughout the dry zone (with a high degree of concentration in the northern and eastern dry zone) indicate that semi-settled communities existed in the island prior to 600 BCE. The megalithic culture was based on a wide range of economic activities, including pottery, the practice of chena cultivation, the rearing of livestock, and the production of hardy iron tools and implements.

The archaeological evidence shows there were close affinities between the megalithic culture complexes and burial sites of Sri Lanka with those of South India. It is therefore tempting to conclude that there was a significant South-Indian presence in the island centuries before the arrival of the northern Indian settlers. However, Senake Bandaranayake (The Peopling of Sri Lanka: The National Question and Some Problems of History and Ethnicity, South Asia Bulletin, 1987) raises the question of whether the migration of ideas and techniques was more important than the migration of peoples in explaining the character and dynamism of Sri Lanka’s internal developments during the prehistoric and early historic periods.

Assuming, on the basis of the megalithic culture complexes, that a cohesive and relatively advanced protohistoric community did exist in Sri Lanka, the question then arises as to how the island had developed a distinct Sinhalese character and ethnos by the 3rd century BCE. The widespread use of the proto-Sinhala language, the dramatic increase in tank irrigation systems, the rapid dissemination of wetland rice cultivation techniques, the establishment of a Sinhalese monarchy and emergence of the early state, the rise of Buddhism: all of these social and cultural phenomena suggest that revolutionary changes occurred in Sri Lanka after the migrants from northern India arrived in the island.