From Tamilakam to Jaffna: A Factual History of Tamil Migration to Sri Lanka

Posted on July 24th, 2025

Shenali D Waduge

The history of Sri Lanka is deeply intertwined with stories of its diverse peoples, among whom the Tamil community is one. Understanding the origins and arrival of Tamils in Sri Lanka is crucial—not only to appreciate the island’s complex cultural mosaic but also to clarify longstanding myths and contested narratives that have shaped political and social discourse creating unwanted animosity. This article explores ten critical perspectives that shed light on the Tamil presence in Sri Lanka, drawing on linguistic evidence, historical records, archaeological findings, and cultural interactions. By examining these facets, a nuanced, evidence-based understanding of how and when Tamils came to inhabit the island, challenges funded versions of history.

This article refutes the claim that Tamils are indigenous to Sri Lanka or that a historical Tamil Eelam” ever existed. Drawing on linguistic, archaeological, genetic, and historical evidence, it shows that Tamil presence came through migration—in waves of traders, medieval invaders, and colonial-era laborers.

There is no record of a Tamil polity predating the Sinhalese Buddhist civilization.

The term Eelam” itself is rooted in Hela” or Elu,” denoting early Sinhalese, not Tamils.

This clarification matters today, as false narratives are used to justify devolution, separatism, and UN interventions. Reclaiming historical accuracy is essential to preserving Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and national identity.

1. Origins of Tamils & their arrival in Sri Lanka

Homeland & Early Contacts

- Tamilakam as Homeland:Tamils evolved in Tamilakam (modern Tamil Nadu, parts of Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Puducherry).

- Sangam Literature (c. 300 BCE–300 CE):Classical Tamil poems center on Tamilakam (Madurai, Kaveri delta)—no reference to any Sri Lankan Tamil polity.

- Early Contacts:From the 3rd century BCE to 5th century CE, small groups of Tamil merchants and mercenaries traded with Anuradhapura but left no evidence of mass settlement.

Colonial Census Term

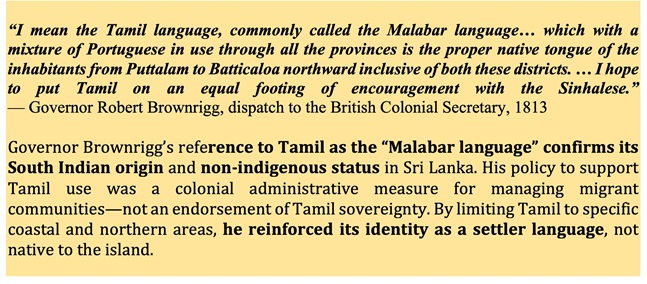

- 1911 Census Distinction:British administrative records replace Malabar Tamils” with Ceylon Tamils” (long‑settled) vs. Indian Tamils” (plantation migrants), explicitly recognizing Tamil migrants from India—not indigenous inhabitants. This was done by then Tamil registrar Ramanathan.

Linguistic Evidence

- Dravidian Roots:Tamil‑Brahmi inscriptions (end of 3rd century BCE) and Ashokan Prakrit loanwords are confined to the Indian mainland.

- Tamil‑Brahmi Graffiti in Sri Lanka:1st–2nd century CE rock‑shelter graffiti are only personal names, not administrative texts—indicating isolated visitors, not a Tamil state.

- Old Sinhala Substratum:Sinhala shows only a handful of Dravidian loanwords, consistent with sporadic contact, not co‑equal coexistence.

Genetic & Toponymic Evidence

- Genetics:Sri Lankan Tamils cluster closely with South Indian Tamils and Telugus, distinct from Veddas and Sinhalese.

- Place‑Names:Authentic Tamil toponyms (suffixes –ur, –kudi) emerge in Northern Sri Lanka only after the 11th century Chola invasions.

Textual & Traveler Accounts

- Mahāvamsa/Cūḷavaṁsa:Pāli chronicles (5th century CE onward) omit any Tamil‑speaking kingdom until the 11th Chola invasions, and elsewhere refer to Tamils only as traders or mercenaries.

- Medieval Travelers:Marco Polo (13th ), Ibn Battuta (14th c.) and Persian merchants describe Tamil merchant enclaves in coastal towns—commercial, not sovereign.

Medieval Tamil Kingdom

- 1215 CE Arya Chakravarti Settlement:South Indian elites establish the Jaffna Kingdom as a settler polity, paying tribute to Sinhalese monarchs (e.g., Parakramabahu II 1236–1270) and later subdued by Prince Sapumal in the mid‑15th century.

Archaeological Record

- Urban Capitals (Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa):No Dravidian temple inscriptions or architecture appear until post-Chola

- Script Continuity:Sri Lankan Tamil inscriptions employ the same South Indian Tamil script, with no unique local evolution.

Summary

All lines of evidence—textual, linguistic, genetic, epigraphic, archaeological, and traveler—unanimously show that Tamils originated in Tamilakam and arrived in Sri Lanka in distinct, migratory waves:

- traders/mercenaries in the early centuries,

- medieval settlers in Jaffna, and

- colonial laborers on the plantations.

There is no indication of an autochthonous Tamil polity predating these migrations.

2. When and how did Tamil settlements in Northern Sri Lanka develop?

- Chola Military Incursions (993 CE & 1017 CE):

- In 993 CE, Rajaraja Iinvaded and conquered Anuradhapura, establishing Polonnaruwa as a Chola provincial capital; by 1017 CE, Rajendra I had fully annexed northern Ceylon as part of the Chola Empire

- In 1070 CE, Vijayabahu I(r. 1070–1110 CE) of Polonnaruwa expelled the Cholas and restored Sinhalese sovereignty over the north and center of the island

- Pre‑Existing Sinhalese/Buddhist Presence:

- Kandarodai (Kadurugoda) Monasteryin the Jaffna Peninsula contains Anuradhapura‑era stupas and an inscription of King Dappula IV (r. 923–935 CE), proving a continuous Sinhalese Buddhist presence there centuries before any settler Tamil kingdom.

- Establishment of the Jaffna Kingdom (c. 1215 CE):

- Around 1215 CE, Magha of Kalingainvaded, followed by the rise of the Arya Chakravarti dynasty—Tamil‑speaking elites from South India—who founded the Jaffna Kingdom as a settler state, never fully independent of Sinhalese over lordship.

- Parakramabahu II(r. 1236–1270 CE) of Dambadeniya records campaigns against the Kalinga Magha” invader but notes that Jaffna rulers paid tribute rather than ruled independently.

- Tributary and Viceroyalty Status:

- In the mid‑15th century (c. 1449–1453 CE), Prince Sapumal Kumaraya, acting on behalf of Parakramabahu VI(r. 1412–1467 CE), conquered Jaffna and governed it as a viceroy, confirming that the Jaffna elite remained subordinate to the Sinhalese crown

- Nature of Tamil Settlements:

- The Jaffna Kingdom was a medieval settler polity, with administrative, religious and social systems imported from Tamil Nadu—it did not evolve from a native Sri Lankan Tamil community.

- No evidence(inscriptions, chronicle references or archaeology) points to any Tamil‑speaking kingdom in northern Sri Lanka before these 11th–13th events.

Together, these points—brief Chola occupations, continuous Sinhalese/Buddhist sites, the settler Ayra Chakravarti dynasty, and their tributary/viceroy status—demonstrate that Tamil settlement in the north was always migratory and subordinate, rather than the emergence of an indigenous Tamil state.

3. What evidence exists of Tamil presence before the Sinhalese?

There is no credible evidence—archaeological, linguistic, or historical—that indicates a Tamil-speaking polity or large-scale Tamil settlement in Sri Lanka before Sinhalese or proto-Sinhalese presence.

Supporting Evidence:

- Ancient Chronicles & Temple Inscriptions

- Mahāvaṃsa and Cūḷavaṃsa(5th century CE onward) make no mention of any Tamil polity until the Chola invasions (1017–1070 CE).

- Prior references to Tamils describe them purely as merchants or soldiers—not rulers.

- Epigraphic and Archaeological Silence

- Tamil-Brahmi inscriptionsfrom the 2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE have been found in Anuradhapura, Trincomalee, Tissamaharama, and Vavuniya districts—mentioning Tamil householders and traders, but not rulers (e.g. Damedas, Veḷir clan names).

- Anaikoddai seal, dated to circa 3rd century BCE, bears the word Ko‑ve‑ta” (Tamil for king”), but it appears to belong to asmall chieftain/trader, not a state.

- Megalithic Culture—Not Tamil Polity

- Megalithic urn burials, Red & Black Ware pottery, from sites likeKantarodai, Manthai, Yan Oya, and Ibbankatuwa date from 1000–400 BCE—

- Notably, atKantarodai (Jaffna Peninsula), a cluster of 22 Buddhist stupas and monastery remains predates Tamil arrival—confirming Sinhalese-Buddhist presence before Tamil settlements.

- Linguistic Substrate in Sinhala

- Old Sinhala retains only alimited number of Dravidian loanwords (e.g., familial terms such as marumakān → munubara), consistent with occasional interaction, not long-standing Tamil communities.

Summary Table

| Evidence Type | Evidence Description | Interpretation |

| Chronicles | No Tamil kings mentioned before 11th century | Tamil presence limited to traders or soldiers |

| Inscriptions | Tamil household names, no administrative texts | Tamil individuals, not polity |

| Archaeology | Megalithic graves, Black & Red Ware pottery | Cultural influence, not state organization |

| Buddhist Monuments | Kantarodai stupas predate Tamil settlements | Sinhalese-Buddhist presence precedes Tamil |

| Linguistic Substratum | Sparse Dravidian loanwords in Sinhala | Sporadic contact, not Tamil-origin dominance |

All available evidence points toward sporadic Tamil presence—as small-scale traders or migrants—prior to the Sinhalese state-building process, but no evidence exists of an indigenous Tamil kingdom, polity, or ruling infrastructure in Sri Lanka before the Sinhalese arrived.

4. What is the Origin and Meaning of the Term Eelam”?

- According to the Madras Tamil Lexicon, the term Eelam” (ஈழம்) is derived from Elu” or Hela,” which are ancient terms referring to the early Sinhalese or proto-Sinhalese peoples of the island. These terms predate Tamil settlement in Sri Lanka and are linguistically and historically rooted in the early Indo-Aryan linguistic sphere of the island.

- Eelam” originally referred to the entire island of Sri Lanka or its early inhabitants and did not possess an exclusive Tamil ethnic connotation.

- The modern appropriation of the term Eelam” by Tamil separatists as a reference to a distinct Tamil homeland is therefore a political rebranding, not a reflection of historical reality.

- Historical inscriptions and archaeological evidence confirm a long-standing Sinhalese presence in the Northern and Eastern regions, including Anuradhapura-era Buddhist ruins in Mannar, Jaffna, and Trincomalee. These further disprove the separatist claim that the North and East were exclusively Tamil.

- The political use of Tamil Eelam” is thus a modern ideological construct, repurposing a term with early Sinhalese roots to manufacture a narrative of exclusive Tamil indigeneity in the North and East — a narrative that disregards centuries of shared and overlapping habitation, trade, religion, and governance under successive Sinhalese kingdoms.

5. If Tamils were brought by Colonial and Medieval Migrations,

How can they claim indigenous rights?

- The majority of Tamils in Sri Lanka today descend from two main waves of migration from South India.

- The first group, later known as Ceylon Tamils” or Jaffna Tamils,” settled during medieval times, particularly from the 13th century onwards, often accompanying South Indian invasions (notably by the Pandyan and Chola dynasties) and through the establishment of the Arya Chakravarti kingdom in the Jaffna Peninsula.

- The second group, referred to as Indian Tamils” or Plantation Tamils,” were brought to Sri Lanka by the British colonial administration in the 19th and early 20th centuries as indentured laborers for tea, coffee, and rubber plantations.

- Although these two groups arrived under different historical contexts and centuries apart, both share the same ethnic and geographic origin — Tamil Nadu in South India. As such, neither group can be regarded as indigenous to Sri Lanka in the anthropological or legal sense of the term.

- The distinction between Ceylon Tamils” and Indian Tamils” is not one of ethnicity but of chronology and colonial classification:

- Period and Purpose of Migration:

- Jaffna Tamils arrived mainly through mercantile movement and conquest during medieval times and gradually integrated into the northern socio-political landscape.

- Plantation Tamils were forcibly relocated by the British for labor exploitation, with little or no prior historical connection to the island.

- Colonial Census and Categorization:

British colonial records categorized these communities separately:

- Ceylon Tamils– Long-settled Tamil-speaking communities in the north and east.

- Indian Tamils– Recent labor migrants concentrated in the central highlands.

- However, this separation was administrative, not based on ethnic or civilizational difference.

- No Basis for Indigenous or Sovereign Claims:

- The fact that both groups are external in origin negates any claim to autochthonous or primordial rights over the land.

- The concept of Tamil Eelam” as a historical homeland is thus unsupported by archaeological or anthropological evidence. Even the early Jaffna Tamil kingdom was a foreign construct arising after the collapse of local Sinhala authority in the north.

Tamil nationalist claims to indigeneity or territorial sovereignty must be critically reassessed in light of this common migratory ancestry. While the Sinhala people have a continuous civilizational and linguistic presence traceable to the pre-Christian era on the island, Tamil presence — whether medieval or colonial — stems from historically documented movements from the Indian mainland.

6. Why was Thesavalamai Law applied to Tamils in Jaffna?

- The Thesavalamai law, codified by the Dutch in 1707, was not an ancient or sovereign Tamil legal system. It was a colonial codification by the Dutch VOC for administrative and commercial purposes, particularly concerning land ownership, inheritance, and marriage.

- Origin and Nature:

- Thesavalamaiwas not transplanted from Tamil Nadu, nor does it reflect a pan-Tamil legal heritage.

- It was not a law used in South Indiaand does not appear in Tamil Nadu’s historical legal tradition.

- The Dutch created this legal code for Tamil settlers in northern Sri Lanka —who had migrated from South India during earlier periods of Chola/Pandya influence and especially during the time of the Arya Chakravarti dynasty.

- Who did it apply to?

- It applied only to Malabar (Tamil) inhabitants of the Jaffna region, as defined by the Dutch.

- The term Malabar” was used by European colonials (Portuguese, Dutch, and British) to refer generally to South Indians,

- It did not apply non-Malabar Tamils living elsewhere in the island, nor to Sinhala, Muslim, or Burgher communities.

- Implications for Sovereignty Claims:

- The very fact that Thesavalamaiwas created by a colonial power undermines the claim that a pre-colonial Tamil kingdom had a structured, sovereign legal system of its own.

- Had there been an unbroken, independent Tamil kingdom in the North at the time of European arrival (like the Sinhala kingdoms in the South and Kandy), there would have been pre-existing, written, codified laws— as we have in Kandyan Lawand Sinhala customary law.

- The Dutch did not codify Sinhala law for the Kandyan Kingdom because they recognized existing indigenous sovereignty. The codification of Thesavalamaiinstead reflects colonial administrative control over a settler community, not recognition of a sovereign Tamil legal system.

Should it still exist?

- Today, Thesavalamai still exists as personal law, applicable to Tamils of Jaffna origin (Malabar heritage only) in matters of property and inheritance.

- However, its continued application raises legitimate questions:

- If this law was designed for a settler community of South Indian origin under Dutch rule, what is its relevance in 21st-century Sri Lanka?

- Why should a colonial law, applicable only to one ethnic group defined by geography and ancestry from South India, continue to have legal standing in a sovereign, unitary republic?

- If Thesavalamaiis recognized, should similar customary or religious laws for other communities also be revived or maintained — or should Sri Lanka move toward a unified civil code?

The existence of Thesavalamai reflects the Dutch colonial need to manage Tamil settler customs in the Jaffna peninsula, not the presence of an ancient Tamil legal or state system. Its continued use today — despite being tied to South Indian colonial-era settlers — invites debate on legal uniformity, national integration, and the risks of ethnic legal exceptionalism.

7. Was there really a separate Tamil Kingdom when the Portuguese arrived?

- What is today referred to as the Jaffna Kingdom” was not an indigenous or sovereign Tamil kingdom in the same sense as the Sinhala kingdoms of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Dambadeniya, or Kandy — which had centuries of continuous rule, written chronicles, and cultural foundations rooted in the island.

- The so-called Jaffna Kingdom” emerged only in the 13th century, following South Indian invasions, notably by the Pandyans and later the Arya Chakravarti dynasty, who were foreign mercenaries or vassals with allegiance to South Indian rulers.

- When the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, they encountered this foreign-established administration in Jaffna, which was swiftly subdued with little or no recorded organized Tamil resistance.

- In sharp contrast, Sinhalese monarchs in Kotte, Sitawaka, and especially the Kingdom of Kandy mounted fierce and sustained resistance to European colonization, often forming complex alliances and engaging in guerrilla warfare.

- The quick collapse of the Arya Chakravarti regime in Jaffna suggests it was isolated, lacked deep-rooted local legitimacy, and did not enjoy the widespread cultural and political support typical of a true native monarchy.

The so-called Tamil kingdom” in Jaffna was not a sovereign, indigenous kingdom comparable to the historical Sinhala polities. Its foreign origin, shallow roots, and lack of resistance to colonization challenge any claim of an unbroken Tamil sovereignty on the island. It was a short-lived outpost of South Indian expansionism, not an ancestral Tamil homeland.

8. Is there Evidence of Sinhalese presence in the North before and during Tamil Settlement?

Yes. Extensive historical, archaeological, and epigraphic evidence confirms a continuous Sinhalese presence and political authority in the Northern Province — long before and even during the period of Tamil settlement and the establishment of the Arya Chakravarti regime in Jaffna.

- Historical Records:

- The Mahavamsa, Sri Lanka’s ancient chronicle (compiled in the 5th century CE), records thatKing Devanampiyatissa (3rd century BCE) sent missions to various parts of the island including Nagadeepa (Jaffna peninsula).

- King Dutugemunu (161–137 BCE)and King Vijayabahu I (1055–1110 CE) are both recorded to have maintained military and administrative control over the northern regions.

- TheCulavamsa (continuation of the Mahavamsa) notes that even during times of South Indian invasions, Sinhalese kings dispatched troops to the North to maintain sovereignty.

- During the reign ofParakramabahu I (1153–1186 CE), extensive irrigation and temple restoration were carried out as far north as Elephant Pass and Jaffna, showing that the region was considered part of the Sinhalese heartland.

- Archaeological Evidence:

- Buddhist ruins, stupas, and inscriptionshave been found across the Northern Province — in Kadurugoda (Kantarodai) in Jaffna, Vavuniya, Murunkan, Nagadipa (Nainativu), Analaitivu, and Mannar.

- TheKadurugoda Buddhist site, near Chunnakam in Jaffna, includes more than 60 ancient stupas made of coral stone, dating back to the Anuradhapura period (3rd century BCE – 10th century CE). Excavations by P.E. Pieris (1917) and later by the Department of Archaeology confirm their Sinhalese-Buddhist origin.

- NumerousBrahmi inscriptions in Sinhala Prakrit have been found in the North and North Central regions, dating from 2nd century BCE onward, confirming early Sinhalese literacy, governance, and religious activity.

- Military and Administrative Control:

- The Vallipuram Gold Plate (2nd century CE), discovered in Jaffna, records a land grant made byKing Vasabha, a Sinhalese monarch of Anuradhapura, to a Buddhist monastery in the area — demonstrating direct royal patronage and authority in the Jaffna peninsula.

- King Vijayabahu Irestored temples in the North and appointed Sinhala governors to maintain order after defeating the Chola invaders.

- Even during the period ofTamil migration and the rise of the Arya Chakravarti dynasty (13th–17th century), Sinhalese kingdoms continued asserting sovereignty, periodically sending military expeditions to the region.

The cumulative evidence — from ancient chronicles, inscriptions, Buddhist monuments, and royal edicts — proves that the Sinhalese were the original inhabitants and rulers of the Northern Province, long before Tamil settlement. Tamil presence, largely resulting from medieval South Indian invasions, did not erase the deep-rooted Sinhala-Buddhist civilization that existed in the North. The narrative of an exclusively Tamil historical homeland in the North is therefore historically inaccurate and politically motivated.

9. Were Tamils ever a Buddhist people — or is Tamil Buddhism” in Sri Lanka a Modern Myth?

- Pre-Hindu Tamil religion revolved around animism and folk deities, not the Buddha, Dhamma, or Sangha. Core Tamil literary texts like the Tolkāppiyam, Akananuru, and Purananurureflect this indigenous belief system, devoid of Buddhist themes.

- Buddhism never took root in Tamilakam (South India); its limited presence came through external patronage(e.g., Pallavas) but faded without lasting institutions or lay communities.

- Any Tamil Buddhist footprint in Sri Lanka was imported through Sinhalese or North Indian channelsand never formed the basis of a Tamil Buddhist state or culture.

- The Jaffna Kingdom was Hindu Shaivite, not Buddhist, and the temples of the North were not viharas but converted into kovilsunder Hindu rule.

- Sites like Kadurugoda (Kantarodai)are often misused by Tamil separatists as proof of Tamil Buddhism,” but archaeology clearly attributes them to Sinhalese-Buddhist origins based on Pali and early Sinhala inscriptions—not Tamil.

- Even leading Tamil historians such as A. Nilakanta Sastriconfirm that Buddhism never deeply penetrated Tamil culture.

There is no historical, religious, or archaeological basis to claim that Tamils were once a Buddhist people or that the North of Sri Lanka was part of a Tamil-Buddhist homeland. This narrative is a modern fabrication aimed at rewriting history to undermine the Sinhalese-Buddhist heritage of the North.

10. What does this mean for contemporary Tamil Nationalist claims?

- TheTamil nationalist narrative of an ancient, indigenous Tamil Eelam” homeland in Sri Lanka lacks historical and linguistic foundation.

- The term Eelam” itself has beenreappropriated for political ends, diverging from its original meaning linked to early Sinhalese inhabitants.

- Both Jaffna Tamils and plantation Tamils havemigrant origins and cannot claim primordial rights to Sri Lankan land.

- Sri Lanka’strue ancestral and indigenous identity is closely tied to the Sinhalese and their ancient civilizations.

Do Tamil Nationalist claims to an ancient homeland in Sri Lanka withstand historical scrutiny?

- The Tamil nationalist claim of an ancient, sovereign Tamil homeland called Eelam” within Sri Lanka is not supported by historical, archaeological, or linguistic evidence.

- The term Eelam” itself was originally associated with the early Sinhalese (Hela/Elu) people and the island of Sri Lanka as a whole — not with a Tamil nation. Its modern use to denote a separate Tamil state is a political rebranding disconnected from its etymological and historical roots.

- Both major Tamil communities in Sri Lanka — the Jaffna Tamils (settled via medieval South Indian invasions) and Plantation Tamils (brought by the British in the 19th century) — have documented migratory origins from Tamil Nadu, not indigenous roots in Sri Lanka.

- Unlike the Sinhalese, whose language, religion (Buddhism), and civilizational identity are organically native to the island for over two millennia, Tamils in Sri Lanka do not possess a continuous, autochthonous cultural lineage grounded in Sri Lankan soil.

- The absence of an ancient Tamil Buddhist kingdom, the foreign origin of the Jaffna regime, and the colonial categorization of Tamils as Malabars or South Indian settlers all weaken the legal and moral basis of any Tamil claim to sovereignty over part of the island.

Tamil nationalist assertions of a historic Tamil Eelam” are rooted in modern political ideology, not historical fact. The Sinhalese are the indigenous people of Sri Lanka, with an unbroken civilizational presence. Calls for Tamil self-determination based on supposed ancestral rights must be re-evaluated in light of the clear migratory origins of Tamil communities and the fabricated nature of the Eelam narrative.

Have Tamils in Sri Lanka ever fought to defend the island from Foreign Invaders?

- Historical evidence shows no major Tamil-led resistance to foreign invasion

- When thePortuguese arrived in the early 16th century, the Arya Chakravarti regime in Jaffna capitulated quickly. There is no recorded mass resistance movement or prolonged Tamil-led defense of Jaffna or the North.

- In contrast,Sinhalese monarchs — from Sitawaka’s Rajasinha I to King Vimaladharmasuriya and later King Rajasinghe II and Sri Vikrama Rajasinha of Kandy — fought prolonged wars against the Portuguese, Dutch, and British to defend sovereignty.

- TheKandyan kingdom, sustained by the Sinhala Buddhist population, was the last bastion of native independence until 1815.

- During British Colonization:

- TheUva-Wellassa rebellion (1818) and Matale rebellion (1848) were Sinhalese-led insurrections against British rule, rooted in defense of land, culture, and Buddhism.

- There isno recorded Tamil uprising against colonial powers in the North or East. Instead, Tamil elites cooperated with colonial administrators, often gaining disproportionately from colonial favoritism in civil service and education.

- Defending the Nation from Terrorism (1980s–2009):

- The 30-year war against theLTTE — a Tamil separatist terrorist movement — was fought almost entirely by the Sinhalese-majority Sri Lankan armed forces.

- Over 95%of the Sri Lanka Army, Navy, and Air Force personnel who sacrificed their lives defending the unity of Sri Lanka were Sinhalese Buddhists.

- While someTamil and Muslim individuals served in the forces, their numbers were marginal relative to their population share. Most Tamils in the North and East were either supportive of the LTTE, intimidated into silence, or passive bystanders — not defenders of Sri Lankan sovereignty.

- Notably,Muslim Home Guards did defend against LTTE attacks in the East, but this was more out of communal self-preservation than national patriotism.

- The Principle: One Defends What One Considers Home

- Historically and psychologically, people fight and die forwhat they consider their own land, identity, and heritage.

- TheSinhalese have proven this repeatedly — from Dutugemunu’s unification campaigns, to resistance against colonialism, to defeating the LTTE in 2009.

- Thelack of comparable Tamil-led defense of Sri Lanka at any stage of invasion or conflict calls into question the Tamil nationalist narrative of deep-rooted indigeneity or national belonging.

Tamils in Sri Lanka have no historical record of defending the island from foreign invasion, colonization, or terrorism on a scale that reflects ownership or deep-rooted belonging.

In contrast, the Sinhalese — particularly the Sinhala Buddhist population — have consistently fought, died, and sacrificed to protect Sri Lanka from foreign and internal threats.

This historical pattern is a powerful indicator of who truly sees this land as their ancestral home.

Shenali D Waduge