Arundhati Roy: Courtesy Financial Times Life & Arts

The

novelist on how coronavirus threatens India — and what the country, and the

world, should do next

Who can use the term gone viral” now without shuddering a little? Who can look at anything any more — a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables — without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?

Who can think of

kissing a stranger, jumping on to a bus or sending their child to school

without feeling real fear? Who can think of ordinary pleasure and not assess

its risk? Who among us is not a quack epidemiologist, virologist, statistician

and prophet? Which scientist or doctor is not secretly praying for a miracle?

Which priest is not — secretly, at least — submitting to science?

And even while

the virus proliferates, who could not be thrilled by the swell of birdsong in

cities, peacocks dancing at traffic crossings and the silence in the

skies?

The number of

cases worldwide this week crept over a million. More than 50,000 people have

died already. Projections suggest that number will swell to hundreds of

thousands, perhaps more. The virus has moved freely along the pathways of trade

and international capital, and the terrible illness it has brought in its wake

has locked humans down in their countries, their cities and their homes. But

unlike the flow of capital, this virus seeks proliferation, not profit, and

has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the

flow. It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and

every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest — thus far — in the

richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism

to a juddering halt. Temporarily perhaps, but at least long enough for us to

examine its parts, make an assessment and decide whether we want to help fix

it, or look for a better engine.

The mandarins

who are managing this pandemic are fond of speaking of war. They don’t even use

war as a metaphor, they use it literally. But if it really were a war, then who

would be better prepared than the US? If it were not masks and gloves that its

frontline soldiers needed, but guns, smart bombs, bunker busters, submarines,

fighter jets and nuclear bombs, would there be a shortage?

Night after night,

from halfway across the world, some of us watch the New York governor’s press

briefings with a fascination that is hard to explain. We follow the statistics,

and hear the stories of overwhelmed hospitals in the US, of underpaid,

overworked nurses having to make masks out of garbage bin liners and old

raincoats, risking everything to bring succour to the sick. About states being

forced to bid against each other for ventilators, about doctors’ dilemmas over

which patient should get one and which left to die. And we think to ourselves,

My God! This is America!”

The tragedy is

immediate, real, epic and unfolding before our eyes. But it isn’t new. It is

the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for years. Who

doesn’t remember the videos of patient dumping” — sick people, still in their

hospital gowns, butt naked, being surreptitiously dumped on street corners?

Hospital doors have too often been closed to the less fortunate citizens of the

US. It hasn’t mattered how sick they’ve been, or how much they’ve suffered.

At least not

until now — because now, in the era of the virus, a poor person’s sickness can

affect a wealthy society’s health. And yet, even now, Bernie Sanders, the

senator who has relentlessly campaigned for healthcare for all, is considered

an outlier in his bid for the White House, even by his own party.

The tragedy

is the wreckage of a train that has been careening down the track for

years

And what of my

country, my poor-rich country, India, suspended somewhere between feudalism and

religious fundamentalism, caste and capitalism, ruled by far-right Hindu

nationalists?

In December,

while China was fighting the outbreak of the virus in Wuhan, the government of

India was dealing with a mass uprising by hundreds of thousands of its citizens

protesting against the brazenly discriminatory anti-Muslim citizenship law it

had just passed in parliament.

The first case

of Covid-19 was reported in India on January 30, only days after the honourable

chief guest of our Republic Day Parade, Amazon forest-eater and Covid-denier

Jair Bolsonaro, had left Delhi. But there was too much to do in February for

the virus to be accommodated in the ruling party’s timetable. There was the

official visit of President Donald Trump scheduled for the last week of the

month. He had been lured by the promise of an audience of 1m people in a sports

stadium in the state of Gujarat. All that took money, and a great deal of

time.

Then there were

the Delhi Assembly elections that the Bharatiya Janata Party was slated to lose

unless it upped its game, which it did, unleashing a vicious, no-holds-barred

Hindu nationalist campaign, replete with threats of physical violence and the

shooting of traitors”.

It lost anyway.

So then there was punishment to be meted out to Delhi’s Muslims, who were

blamed for the humiliation. Armed mobs of Hindu vigilantes, backed by the

police, attacked Muslims in the working-class neighbourhoods of north-east

Delhi. Houses, shops, mosques and schools were burnt. Muslims who had been

expecting the attack fought back. More than 50 people, Muslims and some Hindus,

were killed.

Thousands moved

into refugee camps in local graveyards. Mutilated bodies were still being

pulled out of the network of filthy, stinking drains when government officials

had their first meeting about Covid-19 and most Indians first began to hear

about the existence of something called hand sanitiser.

March was busy too.

The first two weeks were devoted to toppling the Congress government in the

central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and installing a BJP government in its

place. On March 11 the World Health Organization declared that Covid-19 was a

pandemic. Two days later, on March 13, the health ministry said that corona is

not a health emergency”.

Finally, on

March 19, the Indian prime minister addressed the nation. He hadn’t done much

homework. He borrowed the playbook from France and Italy. He told us of the

need for social distancing” (easy to understand for a society so steeped in

the practice of caste) and called for a day of people’s curfew” on March 22.

He said nothing about what his government was going to do in the crisis, but he

asked people to come out on their balconies, and ring bells and bang their pots

and pans to salute health workers.

He didn’t

mention that, until that very moment, India had been exporting protective gear

and respiratory equipment, instead of keeping it for Indian health workers and

hospitals.

Not

surprisingly, Narendra Modi’s request was met with great enthusiasm. There were

pot-banging marches, community dances and processions. Not much social

distancing. In the days that followed, men jumped into barrels of sacred cow

dung, and BJP supporters threw cow-urine drinking parties. Not to be outdone,

many Muslim organisations declared that the Almighty was the answer to the

virus and called for the faithful to gather in mosques in numbers.

On March 24, at

8pm, Modi appeared on TV again to announce that, from midnight onwards, all of

India would be under lockdown. Markets would be closed. All transport, public

as well as private, would be disallowed.

He said he was

taking this decision not just as a prime minister, but as our family elder. Who

else can decide, without consulting the state governments that would have to

deal with the fallout of this decision, that a nation of 1.38bn people should

be locked down with zero preparation and with four hours’ notice? His methods definitely

give the impression that India’s prime minister thinks of citizens as a hostile

force that needs to be ambushed, taken by surprise, but never trusted.

Locked down we

were. Many health professionals and epidemiologists have applauded this move. Perhaps

they are right in theory. But surely none of them can support the calamitous

lack of planning or preparedness that turned the world’s biggest, most punitive

lockdown into the exact opposite of what it was meant to achieve.

The man who

loves spectacles created the mother of all spectacles.

As an appalled

world watched, India revealed herself in all her shame — her brutal,

structural, social and economic inequality, her callous indifference to

suffering.

The lockdown

worked like a chemical experiment that suddenly illuminated hidden things. As

shops, restaurants, factories and the construction industry shut down, as the

wealthy and the middle classes enclosed themselves in gated colonies, our towns

and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens — their migrant

workers — like so much unwanted accrual.

Many driven out

by their employers and landlords, millions of impoverished, hungry, thirsty

people, young and old, men, women, children, sick people, blind people,

disabled people, with nowhere else to go, with no public transport in sight,

began a long march home to their villages. They walked for days, towards

Badaun, Agra, Azamgarh, Aligarh, Lucknow, Gorakhpur — hundreds of kilometres

away. Some died on the way.

Our towns and

megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens like so much unwanted

accrual

They knew they were going home potentially to slow

starvation. Perhaps they even knew they could be carrying the virus with them,

and would infect their families, their parents and grandparents back home, but

they desperately needed a shred of familiarity, shelter and dignity, as well as

food, if not love.

As they walked,

some were beaten brutally and humiliated by the police, who were charged with

strictly enforcing the curfew. Young men were made to crouch and frog jump down

the highway. Outside the town of Bareilly, one group was herded together and

hosed down with chemical spray.

A few days

later, worried that the fleeing population would spread the virus to villages,

the government sealed state borders even for walkers. People who had been

walking for days were stopped and forced to return to camps in the cities they

had just been forced to leave.

Among older

people it evoked memories of the population transfer of 1947, when India was

divided and Pakistan was born. Except that this current exodus was driven by

class divisions, not religion. Even still, these were not India’s poorest

people. These were people who had (at least until now) work in the city and

homes to return to. The jobless, the homeless and the despairing remained where

they were, in the cities as well as the countryside, where deep distress was

growing long before this tragedy occurred. All through these horrible days, the

home affairs minister Amit Shah remained absent from public view.

When the walking

began in Delhi, I used a press pass from a magazine I frequently write for to

drive to Ghazipur, on the border between Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

The scene was

biblical. Or perhaps not. The Bible could not have known numbers such as these.

The lockdown to enforce physical distancing had resulted in the opposite —

physical compression on an unthinkable scale. This is true even within India’s

towns and cities. The main roads might be empty, but the poor are sealed into

cramped quarters in slums and shanties.

Every one of the

walking people I spoke to was worried about the virus. But it was less real,

less present in their lives than looming unemployment, starvation and the

violence of the police. Of all the people I spoke to that day, including a

group of Muslim tailors who had only weeks ago survived the anti-Muslim

attacks, one man’s words especially troubled me. He was a carpenter called

Ramjeet, who planned to walk all the way to Gorakhpur near the Nepal border.

Maybe when

Modiji decided to do this, nobody told him about us. Maybe he doesn’t know

about us”, he said.

Us” means

approximately 460m people.

State

governments in India (as in the US) have showed more heart and understanding in

the crisis. Trade unions, private citizens and other collectives are

distributing food and emergency rations. The central government has been slow

to respond to their desperate appeals for funds. It turns out that the prime

minister’s National Relief Fund has no ready cash available. Instead, money

from well-wishers is pouring into the somewhat mysterious new PM-CARES fund.

Pre-packaged meals with Modi’s face on them have begun to appear.

In addition to

this, the prime minister has shared his yoga nidra videos, in which a morphed,

animated Modi with a dream body demonstrates yoga asanas to help people deal

with the stress of self-isolation.

The narcissism

is deeply troubling. Perhaps one of the asanas could be a request-asana in

which Modi requests the French prime minister to allow us to renege on the very

troublesome Rafale fighter jet deal and use that €7.8bn for desperately needed

emergency measures to support a few million hungry people. Surely the French

will understand.

As the lockdown

enters its second week, supply chains have broken, medicines and essential

supplies are running low. Thousands of truck drivers are still marooned on the

highways, with little food and water. Standing crops, ready to be harvested,

are slowly rotting.

The economic

crisis is here. The political crisis is ongoing. The mainstream media has

incorporated the Covid story into its 24/7 toxic anti-Muslim campaign. An

organisation called the Tablighi Jamaat, which held a meeting in Delhi before

the lockdown was announced, has turned out to be a super spreader”. That is

being used to stigmatise and demonise Muslims. The overall tone suggests that

Muslims invented the virus and have deliberately spread it as a form of

jihad.

The Covid crisis

is still to come. Or not. We don’t know. If and when it does, we can be sure it

will be dealt with, with all the prevailing prejudices of religion, caste and

class completely in place.

Today (April 2)

in India, there are almost 2,000 confirmed cases and 58 deaths. These are

surely unreliable numbers, based on woefully few tests. Expert opinion varies

wildly. Some predict millions of cases. Others think the toll will be far less.

We may never know the real contours of the crisis, even when it hits us. All we

know is that the run on hospitals has not yet begun.

India’s public

hospitals and clinics — which are unable to cope with the almost 1m children

who die of diarrhoea, malnutrition and other health issues every year, with the

hundreds of thousands of tuberculosis patients (a quarter of the world’s

cases), with a vast anaemic and malnourished population vulnerable to any

number of minor illnesses that prove fatal for them — will not be able to cope

with a crisis that is like what Europe and the US are dealing with now.

All healthcare

is more or less on hold as hospitals have been turned over to the service of

the virus. The trauma centre of the legendary All India Institute of Medical

Sciences in Delhi is closed, the hundreds of cancer patients known as cancer

refugees who live on the roads outside that huge hospital driven away like

cattle.

People will fall

sick and die at home. We may never know their stories. They may not even become

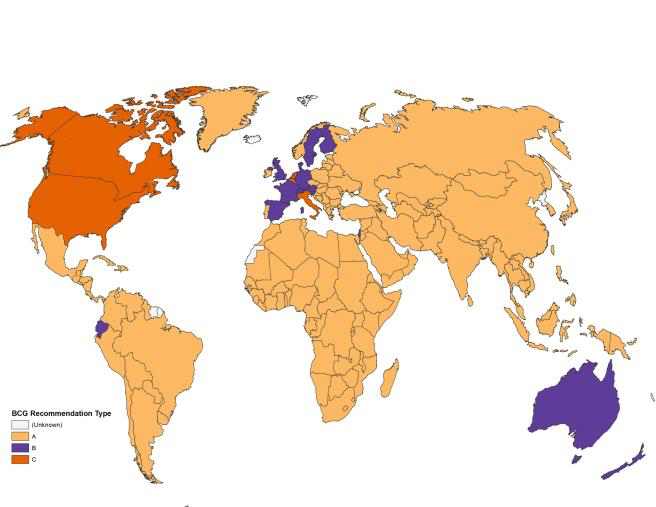

statistics. We can only hope that the studies that say the virus likes cold

weather are correct (though other researchers have cast doubt on this). Never

have a people longed so irrationally and so much for a burning, punishing

Indian summer.

What is this

thing that has happened to us? It’s a virus, yes. In and of itself it holds no

moral brief. But it is definitely more than a virus. Some believe it’s God’s

way of bringing us to our senses. Others that it’s a Chinese conspiracy to take

over the world.

Whatever it is,

coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like

nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a

return to normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to

acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this

terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have

built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

Historically,

pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world

anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and

the next.

We can choose to

walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our

avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind

us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine

another world. And ready to fight for it.

Arundhati Roy’s

latest novel is ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’ Copyright © Arundhati Roy

2020